Communication with the Dead

Distant communication has been transformed since ancient times. People can bridge the distance between absent loved ones by picking up a cellular phone, sending e-mail, or boarding a jet that quickly eradicates physical distance. Nevertheless, technology has not improved communication when it is death that separates individuals. The rich and varied history of attempts to communicate with its tantalizing melange of fact and history continues into the present day.

Attracting and Cherishing the Dead

John Dee fascinated Queen Elizabeth in the middle of the sixteenth century when he provided valuable service to the Crown as a navigational consultant, mathematician, and secret agent. What especially piqued the Queen's interest, though, was Dee's mirror. It was an Aztec mirror that had fallen into his hands—along with its story. Supposedly one could see visions by gazing into the mirror in a receptive state of mind. The Queen was among those who believed she had seen a departed friend in Dee's mirror.

Some claim that the dead choose to communicate with the living and the living can also reach out to them by using special techniques and rituals. These propositions have been accepted by many people since ancient times. Greek religious cults and the Aztecs both discovered the value of reflective surfaces for this purpose.

Raymond A. Moody, best known for his pioneering work on near-death experiences, literally unearthed the ancient tradition when he visited the ruins of a temple known as the Oracle of the Dead. There, on a remote and sacred hilltop in Heraclea, priests could arrange for encounters between the living and the dead. Moody recounts his visit:

The roof of the structure is gone, leaving exposed the maze of corridors and rooms that apparition seekers wandered through while waiting to venture into the apparition chamber. . . . I tried to imagine what this place would have been like two thousand years ago when it was dark as a cave and filled with a kind of eerie anticipation. What did the people think and feel during the weeks they were in here? Even though I like to be alone, my mind boggled at the thought of such lengthy and total sensory deprivation. (Moody 1992, p. 88)

The apparition chamber was the largest room. It was also probably the most majestic and impressive room the visitors had ever seen. After weeks in the dark, they were now bathed in light. Candles flickered against the walls as priests led them toward the centerpiece, a cauldron whose highly polished metal surface glittered and gleamed with reflections. With priestly guidance, the seekers gazed at the mirrored surface and the dead appeared—or did they? No one knows what their eyes beheld. This ritual was persuasive enough, though, that it continued until the temple was destroyed by the conquering Romans. It is reasonable to suppose that some of the living did have profoundly stirring experiences, for they believed themselves to be in contact with loved ones who had crossed to the other side. Dee's Aztec mirror may also have been the stimulus for visions in sixteenth-century England. People thought they were seeing something or somebody.

The crystal ball eventually emerged as the preferred intermediary object. Not everybody was adept. Scryers had the knack of peering into the mystical sphere where they could sometimes see the past and the future, the living and the dead. Meanwhile, in jungle compounds thousands of miles away, there were others who could invoke the dead more directly—through the skull. Bones survived decomposition while flesh rotted away. The skull was, literally, the crowning glory of all bones and therefore embodied a physical link with the spirit of the deceased. It was a treasure to own a hut filled with the skulls of ancestors and perhaps of distinguished members of other tribes. The dead were there all the time and could be called upon for their wisdom and power when the occasion demanded.

Moody attempted to bring the psychomanteum (oracle of the dead) practice into modern times. He created a domestic-sized apparition chamber in his home. He allegedly experienced reunions (some of them unexpected) with his own deceased family members and subsequently invited others to do the same. Moody believed that meeting the dead had the potential for healing. The living and the dead have a second chance to resolve tensions and misunderstandings in their relationship. Not surprisingly, people have responded to these reports as wish-fulfillment illusions and outright hallucinations, depending on their own belief systems and criteria for evidence.

Prayer, Sacrifice, and Conversation

Worship often takes the form of prayer and may be augmented by either physical or symbolic sacrifice. The prayer messages (e.g., "help our people") and the heavy sacrifices are usually intended for the gods. Many prayers, though, are messages to the dead. Ancestor worship is a vital feature of Yoruba society, and Shintoism, in its various forms, is organized around behavior toward the dead.

Zoroastrianism, a major religion that arose in the Middle East, has been especially considerate of the dead. Sacrifices are offered every day for a month on behalf of the deceased, and food offerings are given for thirty years. Prayers go with the deceased person to urge that divine judgment be favorable. There are also annual holidays during which the dead revisit their homes, much like the Mexican Days of the Dead. It is during the Fravardegan holidays that the spirits of the dead reciprocate for the prayers that have been said on their behalf; they bless the living and thereby promote health, fertility, and success. In one way or another, many other world cultures have also looked for favorable responses from the honored dead.

Western monotheistic religions generally have discouraged worship of the dead as a pagan practice; they teach that only God should be the object of veneration. Despite these objections, cults developed around mortals regarded as touched by divine grace. The Catholic Church has taken pains to evaluate the credentials for sainthood and, in so doing, has rejected many candidates. Nevertheless, Marist worship has long moved beyond cult status as sorrowing and desperate women have sought comfort by speaking to the Virgin Mary. God may seem too remote or forbidding to some of the faithful, or a woman might simply feel that another woman would have more compassion for her suffering.

Christian dogma was a work in progress for several centuries. By the fourth century it was decided that the dead could use support from the living until God renders his final judgment. The doctrine of purgatory was subsequently accepted by the church. Masses for the dead became an important part of Christian music. The Gregorian chant and subsequent styles of music helped to carry the fervent words both to God and the dead who awaited his judgment.

Throughout the world, much communication intended for the dead occurs in a more private way. Some people bring flowers to the graveside and not only tell the deceased how much they miss them, but also share current events with them. Surviving family members speak their hearts to photographs of their deceased loved ones even though the conversation is necessarily one-sided. For example, a motorist notices a field of bright-eyed daisies and sends a thought-message to an old friend: "Do you see that, George? I'll bet you can!"

Mediums and Spiritualism

People often find comfort in offering prayers or personal messages to those who have been lost to death. Do the dead hear them? And can the dead find a way to respond? These questions came to the fore during the peak of Spiritualism.

Technology and science were rapidly transforming Western society by the middle of the nineteenth century. These advances produced an anything-is-possible mindset. Inventors Thomas Edison (incandescent light bulb) and Guglielmo Marconi (radio) were among the innovators who more than toyed with the idea that they could develop a device to communicate with the dead. Traditional ideas and practices were dropping by the wayside, though not without a struggle. It was just as industrialization was starting to run up its score that an old idea appeared in a new guise: One can communicate with the spirits of the dead no matter what scientists and authorities might say. There was an urgency about this quest. Belief in a congenial afterlife was one of the core assumptions that had become jeopardized by science (although some eminent researchers remained on the side of the angels). Contact from a deceased family member or friend would be quite reassuring.

Those who claimed to have the power for arranging these contacts were soon known as mediums. Like the communication technology of the twenty-first century, mediumship had its share of glitches and disappointments. The spirits were not always willing or able to visit the séances (French for "a sitting"). The presence of even one skeptic in the group could break the receptive mood necessary to encourage spirit visitation. Mediums who were proficient in luring the dead to their darkened chambers could make a good living by so doing while at the same time providing excitement and comfort to those gathered.

Fascination with spirit contacts swept through much of the world, becoming ever more influential as aristocrats, royalty, and celebrities from all walks of life took up the diversion. The impetus for this movement, though, came from a humble rural American source. The Fox family had moved into a modest home in the small upstate New York town of Hydesville. Life there settled into a simple and predictable routine. This situation was too boring for the young Fox daughters, Margaretta and Kate. Fortunately, things livened up considerably when an invisible spirit, Mr. Splitfoot, made himself known. This spirit communicated by rapping on walls and tables. He was apparently a genial spirit who welcomed company. Kate, for example, would clap her hands and invite Mr. Splitfoot to do likewise, and he invariably obliged.

The girls' mother also welcomed the diversion and joined in the spirit games. In her words:

I asked the noise to rap my different children's ages, successively. Instantly, each one of my children's ages was given correctly . . . until the seventh, at which a longer pause was made, and then three more emphatic raps were given, corresponding to the age of the little one that died, which was my youngest child. (Doyle 1926, vol. 1, pp. 61–65)

The mother was impressed. How could this whatever-it-is know the ages of her children? She invented a communication technique that was subsequently used throughout the world in contacts with the audible but invisible dead. She asked Mr. Splitfoot to respond to a series of questions by giving two raps for each "yes." She employed this technique systematically:

I ascertained . . . that it was a man, aged 31 years, that he had been murdered in this house, and his remains were buried in the cellar; that his family consisted of a wife and five children . . . all living at the time of his death, but that his wife had since died. I asked: "Will you continue to rap if I call my neighbors that they may hear it too?" The raps were loud in the affirmative. . . . (Doyle 1926, vol. 1, pp. 61–65)

And so started the movement known first as Spiritism and later as Spiritualism as religious connotations were added. The neighbors were called in and, for the most part, properly astounded. Before long the Fox sisters had become a lucrative touring show. They demonstrated their skills to paying audiences both in small towns and large cities and were usually well received. The girls would ask Mr. Splitfoot to answer questions about the postmortem well-being of people dear to members of the audience. A few of their skeptics included three professors from the University of Buffalo who concluded that Mr. Splitfoot's rappings were produced simply by the girls' ability to flex their knee-joints with exceptional dexterity. Other learned observers agreed. The New York Herald published a letter by a relative of the Fox family that also declared that the whole thing was a hoax. P. T. Barnum, the great circus entrepreneur, brought the Fox girls to New York City, where the large crowds were just as enthusiastic as the small rural gatherings that had first witnessed their performances.

Within a year or so of their New York appearance, there were an estimated 40,000 Spiritualists in that city alone. People interested in the new Spiritism phenomena often formed themselves into informal organizations known as "circles," a term perhaps derived from the popular "sewing circles" of the time. Many of the Spiritualists in New York City were associated with an estimated 300 circles. Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, and a former Supreme Court judge were among the luminaries who had become supporters of the movement. Mediums also helped to establish a thriving market developed for communication with the beyond. The movement spread rapidly throughout North America and crossed the oceans, where it soon enlisted both practitioners and clients in abundance.

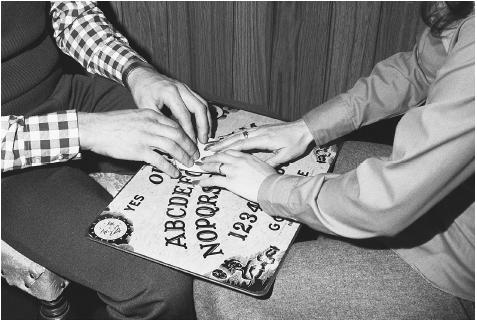

Table-rapping was supplemented and eventually replaced by other communication technologies. The Ouija board was wildly popular for many years. This was a modern derivative of devices that had been used to communicate with the dead 2,500 years ago in China and Greece. The new version started as the planchette, a heart-shaped or triangular, three-legged platform. While moving the device over a piece of paper, one could produce graphic or textual messages. The belief was that the person who operates the device really does not have control over the messages, which is up to the spirits.

The Ouija board was criticized by some as too effective, and, therefore, dangerous. Believers in the spirit world feared that evil entities would respond to the summons, taking the place of the dearly departed. Other critics warned that the "manifestations" did not come from spirits of the dead but rather had escaped from forbidden corners of the user's own mind and could lead to psychosis and suicide.

Fraudulent Communication with the Dead

The quest to communicate with the dead soon divided into two distinct but overlapping approaches. One approach consisted of earnest efforts by people who either longed for contact with their deceased loved ones or were curious about the phenomena. The other approach consisted of outright fraud and chicanery intended to separate emotionally needy and gullible people from their money. Examples of the latter were so numerous that those searching for the truth of the matter were often discouraged. At the same time that modern investigative techniques were being developed, such as those pioneered by Pinkerton detective agency, there was also the emergence of spirit sleuths who devoted themselves to exposing the crooks while looking for any possible authentic phenomena. The famed illusionist Harry Houdini was among the most effective whistle-blowers during the Spiritism movment. Calling upon his technical knowledge in the art of deception, he declared that astounding people with entertaining illusions was very different from claiming supernatural powers and falsely raising hopes about spirit contact.

The long list of deceptive techniques included both the simple and brazen, and the fairly elaborate. Here are a few examples from spirit sleuth John Mulholland:

- • A match-box sized device was constructed to provide a series of "yes" and "no" raps. All the medium had to do was to ask a corresponding series of questions.

- • A blank slate placed on one's head in a darkened room would mysteriously be written upon by a spirit hand. The spirit was lent a hand by a confederate behind a panel who deftly substituted the blank slate for one with a prewritten message.

- • Spirit hands would touch sitters at a séance to lend palpable credibility to the proceedings. Inflatable gloves were stock equipment for mediums.

- • Other types of spirit touches occurred frequently if the medium had but one hand or foot free or, just as simply, a hidden confederate. A jar of osphorized olive oil and skillful suggestions constituted one of the easier ways of producing apparitions in a dark room. Sitters, self-selected for their receptivity to spirits, also did not seem to notice that walking spirits looked a great deal like the medium herself.

- • The growing popularity of photographers encouraged many of the dead to return and pose for their pictures. These apparitions were created by a variety of means familiar to and readily duplicated by professional photographers.

One of the more ingenious techniques was innovated by a woman often considered the most convincing of mediums. Margery Crandon, the wife of a Boston surgeon, was a bright, refined, and likable woman who burgeoned into a celebrated medium. Having attracted the attention of some of the best minds in the city, she sought new ways to demonstrate the authenticity of spirit contact. A high point was a session in which the spirit of the deceased Walter not only appeared but also left his fingerprints. This was unusually hard evidence—until spirit sleuths discovered that Walter's prints were on file in a local dentist's office and could be easily stamped on various objects. Unlike most other mediums, Margery seemed to enjoy being investigated and did not appear to be in it for the money.

Automatic writing exemplified the higher road in attempted spirit communication. This is a dissociated state of consciousness in which a person's writing hand seems to be at the service of some unseen "Other." The writing comes at a rapid tempo and looks as though written by a different hand. Many of the early occurrences were unexpected and therefore surprised the writer. It was soon conjectured that these were messages from the dead, and automatic writing then passed into the repertoire of professional mediums. The writings ranged from personal letters to full-length books. A century later, the spirits of Chopin and other great composers dictated new compositions to Rosemary Brown, a Londoner with limited skills at the piano. The unkind verdict was that death had taken the luster off their genius. The writings provided the basis for a new wave of investigations and experiments into the possibility of authentic communication with the dead. Some examples convinced some people; others dismissed automatic writing as an interesting but nonevidential dissociative activity in which, literally, the left hand did not know what the right hand was doing.

The cross-correspondence approach was stimulated by automatic writing but led to more complex and intensive investigations. The most advanced type of cross-correspondence is one in which the message is incomplete until two or more minds have worked together without ordinary means of communication—and in which the message itself could not have been formulated through ordinary means of information exchange. One of the most interesting cross-correspondence sequences involved Frederick W. H. Myers, a noted scholar who had made systematic efforts to investigate the authenticity of communication with the dead. Apparently he continued these efforts after his death by sending highly specific but fragmentary messages that could not be completed until the recipients did their own scholarly research. Myers also responded to questions with the knowledge and wit for which he had been admired during his life. Attempts have been made to explain cross-correspondences in terms of telepathy among the living and to dismiss the phenomena altogether as random and overinterpreted. A computerized analysis of cross-correspondences might at least make it possible to gain a better perspective on the phenomena.

The Decline of Spiritism

The heyday of Spiritism and mediums left much wreckage and a heritage of distrust. It was difficult to escape the conclusion that many people had such a desire to believe that they suspended their ordinary good judgment. A striking example occurred when Kate Fox, in her old age, not only announced herself to have been a fraud but also demonstrated her repertoire of spirit rappings and knockings to a sold-out audience in New York City. The audience relished the performance but remained convinced that Mr. Splitfoot was the real thing. Mediumship, having declined considerably, was back in business after World War I as families grieved for lost fathers, sons, and brothers. The intensified need for communication brought forth the service.

Another revival occurred when mediums, again out of fashion, were replaced by channelers. The process through which messages are conveyed and other associated phenomena have much in common with traditional Spiritism. The most striking difference is the case of past life regression in which it is the individual's own dead selves who communicate. The case of Bridey Murphy aroused widespread interest in past-life regression and channeling. Investigation of the claims for Murphy and some other cases have resulted in strong arguments against their validity.

There are still episodes of apparent contact with the dead that remain open for wonder. One striking example involves Eileen Garrett, "the skeptical medium" who was also a highly successful executive. While attempting to establish communication with the recently deceased Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, she and her companions were startled and annoyed by an interruption from a person who gave his name as "Flight Lieutenant H. Carmichael Irwin." This flight officer had died in the fiery crash of dirigible R101. Garrett brought in an aviation expert for a follow-up session with Irwin, who described the causes of the crash in a degree of detail that was confirmed when the disaster investigation was completed months later.

The Psychic Friends Network and television programs devoted to "crossing over" enjoy a measure of popularity in the twenty-first century, long after the popularity of the Spiritualism movement. Examples such as these as well as a variety of personal experiences continue to keep alive the possibility of communication with the dead—and perhaps possibility is all that most people have needed from ancient times to the present.

See also: Days of the Dead ; Ghost Dance ; Ghosts ; Near-Death Experiences ; Necromancy ; Spiritualism Movement ; Virgin Mary, the ; Zoroastrianism

Bibliography

Barrett, William. Death-Bed Visions: The Psychical Experiences of the Dying. 1926. Reprint, Northampshire, England: Aquarian Press, 1986.

Bernstein, Morey. The Search for Bridey Murphy. New York: Pocket Books, 1965.

Brandon, Samuel George Frederick. The Judgment of the Dead. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1967.

Covina, Gina. The Ouija Book. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979.

Douglas, Alfred. Extrasensory Powers: A Century of Psychical Research. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 1977.

Doyle, Arthur Conan. The History of Spiritualism. 2 vols. London: Cassell, 1926.

Garrett, Eileen J. Many Voices: The Autobiography of a Medium. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1968.

Hart, Hallan. The Enigma of Survival. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1959.

Kastenbaum, Robert. Is There Life after Death? New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1984.

Kurtz, Paul, ed. A Skeptic's Handbook of Parapsychology. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1985.

Moody, Raymond A. "Family Reunions: Visionary Encounters with the Departed in a Modern Psychomanteum." Journal of Near-Death Studies 11 (1992):83–122.

Moody, Raymond A. Life After Life. Atlanta: Mockingbird Books, 1975.

Myers, Frederick W. H. Human Personality and Its Survival of Death. 2 vols. 1903. Reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1975.

Podmore, Frank. The Newer Spiritualism. 1910. Reprint, New York: Arno, 1975.

Richet, Charles. Thirty Years of Psychical Research. London: Collins, 1923.

Saltmarsh, Herbert Francis. Evidence of Personal Survival from Cross Correspondences. 1938. Reprint, New York: Arno, 1975.

Tietze, Thomas R. Margery. New York: Harper & Row, 1973.

ROBERT KASTENBAUM

Over the past four months, I notice that communications with the deceased is much harder. I often need to struggle to listen to what they are saying, and it becomes frustrating at times. Evidently, other psychics I know are experiencing the same issue.

Do you know of any prayers or rituals which will ease communications between their world and ours?