Widows in Third World Nations

In many traditional communities of developing countries (especially on the Indian subcontinent and in Africa), widowhood represents a "social death" for women. It is not merely that they have lost their husbands, the main breadwinner and supporter of their children, but widowhood robs them of their status and consigns them to the very margins of society where they suffer the most extreme forms of discrimination and stigma.

Widows in these regions are generally the poorest of the poor and least protected by the law because their lives are likely to be determined by local, patriarchal interpretations of tradition, custom, and religion. Unmarried women are the property and under the control of their fathers; married women belong to their husbands. Widows are in limbo and no longer have any protector.

Across cultures they become outcasts and are often vulnerable to physical, sexual, and mental abuse. It as if they are in some way responsible for their husband's death and must be made to suffer for this calamity for the remainder of their lives. Indeed, it is not uncommon for a widow—especially in the context of the AIDS pandemic—to be accused of having murdered her husband, for example, by using witchcraft.

The grief that many third world widows experience is not just the sadness of bereavement but the realization of the loss of their position in the family that, in many cases, results in their utter abandonment, destitution, and dishonor.

In some African cultures, death does not end a marriage, and a widow is expected to move into a "levirate" arrangement with her brother-in-law ("the levir") or other male relative or heir nominated by his family. The children conceived are conceived in the name of the dead man. In other ethnic groups she may be "inherited" by the heir. Many widows resist these practices, which are especially repugnant and also life threatening in the context of AIDS and polygamy. Refusal to comply may be answered with physical and sexual violence. While in earlier times such traditional practices effectively guaranteed the widow and her children protection, in recent decades, because of increasing poverty and the breakup of the extended family, widows discover that there is no protection or support, and, pregnant by the male relative, they find themselves deserted and thrown out of the family homestead for good.

Widowhood has a brutal and irrevocable impact on a widow's children, especially the girl child. Poverty may force widows to withdraw children from school, exposing them to exploitation in child labor, prostitution, early forced child marriage, trafficking, and sale. Often illiterate, ill-equipped for gainful employment, without access to land for food security or adequate shelter, widows and their children suffer ill health and malnutrition, lacking the means to obtain appropriate health care or other forms of support.

However, there is an astonishing ignorance about and lack of public concern for the suffering of widows and their families on the part of governments, the international community, and civil society, and even women's organizations. In spite of four UN World Women's Conferences (Mexico 1975, Copenhagen 1980, Nairobi 1985, and Beijing 1995) and the ratification by many countries of the 1979 UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), widows are barely mentioned in the literature of gender and development, except in the context of aging. Yet the issues of widowhood cut across every one of the twelve critical areas of the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action, covering poverty, violence to women, the girl child, health, education, employment, women and armed conflict, institutional mechanisms, and human rights.

One explanation for the neglect of this vast category of abused women is the assumption that widows are mainly elderly women who are cared for and respected by their extended or joint families. In fact, of course, far from caring for and protecting widows, male relatives are likely to be the perpetrators of the worst forms of widow abuse. If they are young widows, it is imagined that they will be quickly remarried. In fact, millions of widows are very young when their husbands die but may be prevented by custom from remarrying, even if they wish to do so.

But in spite of the numbers involved, little research on widows' status exists (the Indian Census of 1991 revealed 35 million widows, but very little statistical data has been collected for other developing countries). Despite a mass of anecdotal and narrative information, public policies have not developed to protect widows' rights. Despite the poverty that widows and their children experience, organizations such as the World Bank have not yet focused on this hidden section in populations.

Laws, Customs, Tradition, and Religion

Across cultures, religions, regions, class, and caste, the treatment of widows in many developing countries, but especially in the South Asian subcontinent and in Africa, is harshly discriminatory.

Patriarchal kinship systems, patrilocal marriage (where the bride goes to the husband's location), and patrilineal inheritance (where succession devolves through the male line) shore up the concept that women are "chattels" who cannot inherit and may even be regarded as part of the husband's estate to be inherited themselves (widow inheritance). Where matrilineal kinship systems pertain, inheritance still devolves onto the males, through the widow's brother and his sons.

Disputes over inheritance and access to land for food security are common across the continents of South Asia and Africa. Widows across the spectrum of ethnic groups, faiths, regions, and educational and income position share the traumatic experience of eviction from the family home and the seizing not merely of household property but even intellectual assets such as pension and share certificates, wills, and accident insurance.

"Chasing-off" and "property-grabbing" from widows is the rule rather than the exception in many developing countries. These descriptive terms have been incorporated into the vernacular languages in many countries, and even (e.g., Malawi) used in the official language in new laws making such actions a crime.

The CEDAW or "Women's Convention" and the Beijing Global Platform for Action require governments to enact and enforce new equality inheritance laws. Some governments have indeed legislated to give widows their inheritance rights. But even where new laws exist, little has changed for the majority of widows living in the South Asian subcontinent and in Africa. A raft of cultural, fiscal, and geographical factors obstructs any real access to the justice system. Widows from many different regions are beginning to recount their experiences of beatings, burnings, rape, and torture by members of their husbands' families, but governments have been slow to respond, their silence and indifference, in a sense, condoning this abuse.

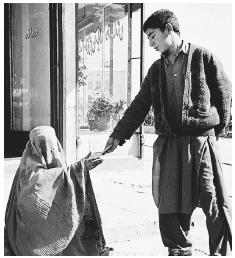

In India, many laws to protect women have been passed since independence. But it is the personal laws of each religious community that govern property rights and widowhood practices. The world knows of the practice of widow-burning ( sati ), but little of the horrors widows suffer within the confines of their relatives' homes, how they are treated by their communities, or their fate when abandoned to the temple towns to survive by begging and chanting prayers. There are approximately 20,000 widows in Vrindavan, the holy city; Varanasi; Mathura; and Haridwar.

Common to both regions are interpretations of religious laws, customs, and traditions at the local level that take precedence over any modern state or international law. Widows in any case, especially the millions of illiterate widows living in rural areas, are mostly ignorant of the legal rights they have.

Mourning and Burial Rites

All human societies have sought ways to make death acceptable and to provide opportunities for expressing grief and showing respect to the dead person. In societies where the status of women is low, the mourning and burial rituals are inherently gendered. Rituals are used to exalt the position of the dead man, and his widow is expected to grieve openly and demonstrate the intensity of her feelings in formalized ways. These rituals, prevalent in India as well as among many ethnic groups in Africa, aim at exalting the status of the deceased husband, and they often incorporate the most humiliating, degrading, and life-threatening practices, which effectively punish her for her husband's death.

For example, in Nigeria specifically (but similar customs exist in other parts of Africa), a widow may be forced to have sex with her husband's brothers, "the first stranger she meets on the road," or some other designated male. This "ritual cleansing by sex" is thought to exorcise the evil spirits associated with death, and if the widow resists this ordeal, it is believed that her children will suffer harm. In the context of AIDS and polygamy, this "ritual cleansing" is not merely repugnant but also dangerous. The widow may be forced to drink the water that the corpse has been washed in; be confined indoors for up to a year; be prohibited from washing, even if she is menstruating, for several months; be forced to sit naked on a mat and to ritually cry and scream at specific times of the day and night. Many customs causes serious health hazards. The lack of hygiene results in scabies and other skin diseases; those who are not allowed to wash their hands and who are made to eat from dirty, cracked plates may fall victim to gastroenteritis and typhoid. Widows who have to wait to be fed by others become malnourished because the food is poorly prepared.

In both India and Africa, there is much emphasis on dress and lifestyles. Higher-caste Hindu widows must not oil their hair, eat spicy food, or wear bangles, flowers, or the "kumkum" (the red disc on the forehead that is the badge of marriage). Across the cultures, widows are made to look unattractive and unkempt. The ban on spicy foods has its origins in the belief that hot flavors make a widow more lustful. Yet it is widows who are often victims of rape, and many of the vernacular words for "widow" in India and Bangladesh are pejorative and mean "prostitute," "witch," or "sorceress." The terrible stigma and shame of widowhood produces severe depression in millions of women, and sometimes suicide.

Widowhood in the Context of AIDS

AIDS has resulted in a huge increase in widows, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. For sociological and biological reasons, women are twice as likely to contract HIV through vaginal intercourse as men. In southern Africa, the rates of infection for young women between ten and twenty-four years old are up to five times higher than for young men. This is significant for widows for a number of reasons. In addition to the normal social practice of older men marrying far younger women that prevails in some communities, there is a belief, held by many men, that having sex with a young girl or virgin will cure men of their HIV infection or protect them from future exposure. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this myth has significantly increased the incidence of child marriage and child rape. Such early marriage does not bring security but serious risk and vulnerability to infection. Married thirteen- to nineteen-year-old women in Uganda are twice as likely to be HIV-positive as their single contemporaries. These child brides quickly become child widows bearing all the stigma of widowhood, the problems compounded by their youth and helplessness.

Widows whose husbands have died of AIDS are frequently blamed for their deaths because of promiscuity, whereas, in the majority of cases, it is the men who have enjoyed multiple sex partners but return home to be nursed when they fall ill. These widows may or may not be aware of their sero-positive (infected with the HIV/AIDS virus) status and may reject being tested, fearing the consequences of a positive result, which, with no access to modern drugs, can amount to a death sentence. Besides, the dying husband's health care will, in most cases, have used up all available financial resources so that the widow is unable to buy even the basic medicines or nutritious food needed to relieve her condition.

AIDS widows, accused of murder and witchcraft, may be hounded from their homes and subject to the most extreme forms of violence. A Help Age International Report from Tanzania revealed that some 500 older women, mostly widowed in the context of AIDS, were stoned to death or deliberately killed in 2000.

The poverty of AIDS widows, their isolation and marginalization, impels them to adopt high-risk coping strategies for survival, including prostitution, which spreads HIV. In the struggle against poverty, the abandonment of female children to early marriage, child sex work, or sale for domestic service is common because the girl, destined to marry "away" at some point in her life, has no economic value to her mother.

But widows are not exclusively victims— millions of surviving AIDS widows, especially the grandmothers, make exceptional but unacknowledged contributions to society through child care, care of orphans, agricultural work, and sustaining the community.

The international community, and especially the UN agencies such as WHO and UNAIDS, need to address the impact of AIDS on widowhood. So far, epidemiological studies have ignored them,

Widowhood through Armed Conflict and Ethnic Cleansing

Sudden, cruel bereavement through war, armed conflict, and ethnic cleansing is the shared trauma of hundreds of thousands of women across the globe. Widowhood is always an ordeal for women, but for war widows the situation is infinitely worse. Widows from Afghanistan, Mozambique, Angola, Somalia, Cambodia, Vietnam, Uganda, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Bosnia, Kosovo, Sri Lanka, East Timor, Guatemala—old women and young mothers— provide testimonies of brutalities, rapes, homelessness, terror, and severe psychological damage.

There are a few actual statistics for individual countries on numbers of widows, but it is estimated that, for example, in Rwanda, following the genocide of 1994, over 70 percent of adult women were widowed. In Mozambique, following the civil war, over 70 percent of children were thought to be dependent on widowed mothers. Widows of war are often uncounted and invisible. Many widows, survivors of ethnic cleansing, have been victims of gang rapes or witnessed the death of husbands, sons, parents, and siblings. They eke out a bleak existence as traumatized, internally displaced persons or languish in sordid refugee camps, having lost not just their bread winner and male protector but also their worldly possessions. In the postconflict period, they remain in danger. To add to their problems, widows who have survived terrible hardships are often abandoned or ostracized by their relatives who refuse to support them. The shame of rape, the competition for scarce resources such as the family land or the shared house, places conflict widows in intense need. They are unable to prove their title to property and typically have no documentation and little expert knowledge about their rights. They bear all the burden of caring for children, orphans, and other surviving elderly and frail relatives without any education or training to find paid work. Widows in third world nations have the potential to play a crucial role in the future of their societies and the development of peace, democracy, and justice, yet their basic needs and their valuable contributions are mostly ignored. Where progress has been made, it is due to widows working together in an association.

Widows' Coping Strategies

What do widows do in countries where there is no social security and no pensions, and where the traditional family networks have broken down? If they do not surrender to the demands of male relatives (e.g., "levirate," widow inheritance, remarriage, household slavery, and often degrading and harmful traditional burial rites) and they are illiterate and untrained and without land, their options are few. Often there is no alternative to begging except entering the most exploitative and unregulated areas of informal sector labor, such as domestic service and sex work. Withdrawing children from school, sending them to work as domestic servants or sacrificing them to other areas of exploitative child labor, selling female children to early marriages or abandoning them to the streets, are common survival strategies and will continue to be used until widows can access education and income-generating training for themselves and their dependents.

Looking to the Future: Progress and Change

When widows "band together," organize themselves, make their voices heard, and are represented on decision-making bodies locally, nationally, regionally, and internationally, change will occur. Progress will not be made until widows themselves are the agents of change. Widows' associations must be encouraged and "empowered" to undertake studies profiling their situation and needs. They must be involved in the design of projects and programs and instrumental in monitoring the implementation and effectiveness of new reform legislation to give them property, land, and inheritance rights; protect them from violence; and give them opportunities for training and employment.

Widows at last have an international advocacy organization. In 1996, following a workshop at the Beijing Fourth World Women's Conference, Empowering Widows in Development (EWD) was established. This nongovernmental international organization has ECOSOC consultative status with the United Nations and is a charity registered in the United Kingdom and the United States. It is an umbrella group for more than fifty grass-roots organizations of widows in South Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, and East Asia and its membership is constantly growing. EWD is focusing on the plight of millions of widows in Afghanistan—Afghan widows in refugee camps. An offshoot of EWD, Widows For Peace and Reconstruction, was set up in August, 2001 to represent the special needs of war widows and to ensure that their voices are heard in post-conflict peace building.

In February 2001 EWD held its first international conference, "Widows Without Rights," in London; participants, widows' groups, and their lawyers came from some fifteen different countries. EWD represents widows at UN meetings, such as the UN Commission on the Status of Women, and is a consultant to various UN agencies on issues of widowhood. At last, widows are becoming visible, and their groups, both grass roots and national, are beginning to have some influence within their countries.

However, much more work is needed to build up the capacity of widows' groups and to educate the United Nations, civil society, governments, and institutions, including the judiciary and the legal profession, on the importance of protecting the human rights of widows and their children in all countries, whether they are at peace or in conflict.

See also: Gender and Death ; Widowers ; Widows

Bibliography

Chen, Marthy, and Jean Dreze. Widows and Well-Being in Rural North India. London: London School of Economics, 1992.

Dreze, Jean. Widows in Rural India. London: London School of Economics, 1990.

Owen, Margaret. "Human Rights of Widows in Developing Countries." In Kelly D. Askin and Dorean M. Koenig, eds., Women and International Human Rights Law New York: Transnational Publishers, 2001.

Owen, Margaret. AWorld of Widows. London: ZED Books, 1996.

Potash, Betty, ed. Widows in African Societies: Choices and Constraints. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1986.

Internet Resources

Division for the Advancement for Women. "Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action." In the United Nations [web site]. Available from www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/platform/index.html .

MARGARET OWEN