Life Expectancy

Life expectancy refers to the number of years that people in a given country or population can expect to live. Conceptually, life expectancy and longevity are identical; the difference between them lies in measurement issues. Life expectancy is calculated in a very precise manner, using what social scientists call "life table analysis." Longevity is not associated with any particular statistical technique. Both life expectancy and longevity are distinct from life span, which refers to the number of years that humans could live under ideal conditions. While life expectancy is based on existing data, life span is speculative. Partly because of its speculative nature, there is considerable debate about the possible length of the human life span. Some social scientists argue that Western populations are approaching a biologically fixed maximum, or finite life span, probably in the range of 85 to 100 years. Others believe that the human life span can be extended by many more years, due to advances in molecular medicine or dietary improvements, for example. An intermediate position is taken by other researchers, who suggest that there is no rigid limit to the human life span and as-yet-unforeseen biomedical technological breakthroughs could gradually increase life span.

A considerable amount of research, based on the foundational assumption of a finite human life span, has focussed on the concept of dependency-free life expectancy (also called dependence-free life expectancy, healthy life expectancy, active life expectancy, disability-free life expectancy, and functional life expectancy). These varying terms refer to the number of years that people in a given population can expect to live in reasonably good health, with no or only minor disabling health conditions. Most of the research on dependency-free life expectancy tests, in varying ways, the validity of the compression of morbidity hypothesis, originally formulated by the researcher James F. Fries in 1983. This hypothesis states that, at least among Western populations, proportionately more people are able to postpone the age of onset of chronic disability; hence, the period of time between onset of becoming seriously ill or disabled and dying is shortening or compressing. Research findings on morbidity compression are variously supportive, negative, and mixed.

The Measurement of Life Expectancy

Life expectancy is a summary measure of mortality in a population. Statistics on life expectancy are derived from a mathematical model known as a life table. Life tables create a hypothetical cohort (or group) of 100,000 persons (usually of males and females separately) and subject it to the age-sex-specific mortality rates (the number of deaths per 1,000 or 10,000 or 100,000 persons of a given age and sex) observed in a given population. In doing this, researchers can trace how the 100,000 hypothetical persons (called a synthetic cohort) would shrink in numbers due to deaths as they age. The average age at which these persons are likely to have died is the life expectancy at birth. Life tables also provide data on life expectancy at other ages; the most commonly used statistic other than life expectancy at birth is life expectancy at age sixty-five, that is, the number of remaining years of life that persons aged sixty-five can expect to live.

Life expectancy statistics are very useful as summary measures of mortality, and they have an intuitive appeal that other measures of mortality, such as rates, lack. However, it is important to interpret data on life expectancy correctly. If it reported that life expectancy at birth in a given population is 75 years in 2000, this does not mean that all members of the population can expect to live to the age of 75. Rather, it means that babies born in that population in 2000 would have a life expectancy at birth of 75 years, if they live their lives subject to the age-specific mortality rates of the entire population in 2000. This is not likely; as they age, age-specific mortality rates will almost certainly change in some ways. Also, older people in that population will have lived their life up to the year 2000 under a different set of age-specific mortality rates. Thus, it is important to be aware of the hypothetical nature of life expectancy statistics.

Life tables require accurate data on deaths (by age and sex) and on the population (by age and sex); many countries lack that basic data and their life expectancy statistics are estimates only. However, age-specific mortality tends to be very predictable; thus, if the overall level of mortality in a population is known, it is possible to construct quite reasonable estimates of life expectancy using what are called model life tables.

Life Expectancy at Birth, Circa 2001

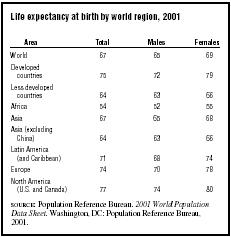

Life expectancy at birth for the world's population at the turn of the twenty-first century was 67 years, with females having a four-year advantage (69 years) over males (65 years); see Table 1. As expected, developed countries experience substantially higher life expectancy than less developed countries—75 years and 64 years, respectively.

| Life expectancy at birth by world region, 2001 | |||

| Area | Total | Males | Females |

| World | 67 | 65 | 69 |

| Developed countries | 75 | 72 | 79 |

| Less developed countries | 64 | 63 | 66 |

| Africa | 54 | 52 | 55 |

| Asia | 67 | 65 | 68 |

| Asia (excluding China) | 64 | 63 | 66 |

| Latin America (and Caribbean) | 71 | 68 | 74 |

| Europe | 74 | 70 | 78 |

| North America (U.S. and Canada) | 77 | 74 | 80 |

| SOURCE : Population Reference Bureau. 2001 World Population Data Sheet. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau, 2001. | |||

Also, the gender difference in life expectancy that favors females is larger in the developed countries (seven years) than in the less developed parts of the world (three years). Regionally, North America (the United States and Canada) has the highest life expectancy overall, and for males and females separately. It might be expected that Europe would have this distinction and, indeed, there are a number of European countries with life expectancies higher than in North America; for example, the Scandinavian countries and the nations of Western Europe. However, the European average is pulled down by Russia; in 2001, this large country of 144 million people has a male life expectancy at birth of only 59 years and a female life expectancy at birth of 72 years. Male life expectancy in Russia declined over the last decades of the twentieth century, and shows no indication of improvement. A considerable amount of research has focused on the trend of increasing mortality (and concomitant decreasing life expectancy) among Russian men, pointing to a number of contributing factors: increased poverty since the fall of communism, which leads to malnutrition, especially among older people, and increases susceptibility to infectious diseases; unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, including heavy drinking and smoking, sedentary living, and high-fat diets; psychological stress, combined with heavy alcohol consumption, leading to suicide; and a deteriorating health care system.

With the exception of Russia (and Eastern Europe more generally), life expectancy at birth does not vary much within European and North American populations. However, the less developed countries have considerably more range in mortality, as measured by life expectancy at birth. This can be seen in Table 1, which shows a range in life expectancy at birth among females from 55 in Africa to 74 in Latin America. It is clear that Africa lags behind the rest of the world in achieving improvements in life expectancy. However, even within Africa, large differences in life expectancy exist. Life expectancy at birth (both sexes combined) statistics range from the low seventies (in Mauritius (71), Tunisia (72) and Libya (75)) to the low forties (in Swaziland and Zimbabwe (both 40), Niger and Botswana (both 41)) with one country—Rwanda—having an estimated life expectancy at birth of only 39 years.

Life Expectancy at Birth in African Countries: The Role of HIV/AIDS

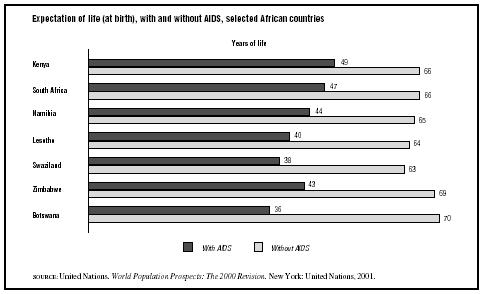

The HIV/AIDS (human immunodeficiency virus/ acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) epidemic has, thus far, hit hardest in parts of Africa, especially sub-Saharan Africa, which contains approximately 70 percent of the world's population with HIV/AIDS. Many of the African countries with the lowest life expectancies have the highest rates of HIV/AIDS infection. However, this is not always the case; for example, Niger and Rwanda, mentioned above as countries with very low life expectancies, do not have high rates of HIV/AIDS in their populations. Thus, AIDS cannot solely account for low life expectancy in Africa; social and political upheaval, poverty, and the high risk of death due to other infectious (and parasitic) diseases cannot be discounted in the African case. Nevertheless, HIV/AIDS does have a devastating impact on life expectancy in many places in Africa. The United Nations projects that by 2050 the effect of the AIDS epidemic will be to keep life expectancy at birth low in many sub-Saharan African countries, perhaps even lower than that experienced in the latter part of the twentieth century. Figure 1 shows two projected life expectancy at birth statistics for seven sub-Saharan African countries, one based on the assumption that HIV/AIDS continues to claim lives prematurely, and the other based on the optimistic assumption that HIV/AIDS was to disappear immediately. The effect of HIV/AIDS is to keep life expectancy in 2050 at levels well under 50; in the absence of the pandemic, life expectancy at birth would improve to the 65 to 70 year range. The projections based on the continuation of HIV/AIDS mark a sad departure for the demographers who make them. Until the 1990s, projections were based on a taken-for-granted assumption that life expectancy would gradually improve. And, for the most part, subsequent mortality trends backed up that assumption.

Trends in Life Expectancy at Birth in Developed Countries

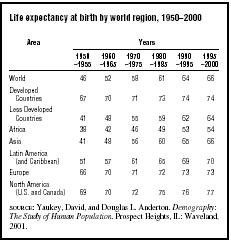

In the developed countries, the fragmentary data that are available suggest that life expectancy at birth was around 35 to 40 years in the mid-1700s, that it rose to about 45 to 50 by the mid-1800s, and that rapid improvements began at the end of the nineteenth century, so that by the middle of the twentieth century it was approximately 66 to 67 years. Since 1950 gains in life expectancy have been smaller, approximately eight more years have been added (see Table 2).

The major factors accounting for increasing life expectancy, especially in the period of rapid improvement, were better nutrition and hygiene practices (both private and public), as well as enhanced knowledge of public health measures. These advances were particularly important in lowering infant mortality; when mortality is not controlled, the risk of death is high among infants and young children (and their mothers), and the major cause of death is infectious diseases (which are better fought off by well-fed infants and children). Being that a large proportion of deaths occurs to infants and young children, their improved longevity plays a key role in increasing life expectancy at birth. The period from the late 1800s to 1950 in the West, then, saw significant improvement in the mortality of infants and children (and their mothers); it was reductions in their mortality that led to the largest increases in life expectancy ever experienced in developed countries. It is noteworthy that medical advances, save for smallpox vaccination, played a relatively small role in reducing infant and childhood mortality and increasing life expectancy.

Since the middle of the twentieth century, gains in life expectancy have been due more to

Trends in Life Expectancy in Less Developed Countries

Very little improvement in life expectancy at birth had occurred in the third world by the middle of the twentieth century. Unlike the developed countries, which had a life expectancy at birth of 67

| Life expectancy at birth by world region, 1950–2000 | ||||||

| Area | Years | |||||

|

1950

–1955 |

1960

–1965 |

1970

–1975 |

1980

–1985 |

1990

–1995 |

1995

–2000 |

|

| World | 46 | 52 | 58 | 61 | 64 | 66 |

| Developed Countries | 67 | 70 | 71 | 73 | 74 | 74 |

| Less Developed Countries | 41 | 48 | 55 | 59 | 62 | 64 |

| Africa | 38 | 42 | 46 | 49 | 53 | 54 |

| Asia | 41 | 48 | 56 | 60 | 65 | 66 |

| Latin America (and Caribbean) | 51 | 57 | 61 | 65 | 69 | 70 |

| Europe | 66 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 73 |

| North America (U.S. and Canada) | 69 | 70 | 72 | 75 | 76 | 77 |

| SOURCE : Yaukey, David, and Douglas L. Anderton. Demography: The Study of Human Population. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland, 2001. | ||||||

years at that time, the third world's life expectancy approximated 41 years—a difference of 26 years. However, after the end of World War II, life expectancy in the developing countries began to increase very rapidly. For example, between 1950 and 1970, life expectancy at birth improved by 14 years (see Table 2). Mortality decline was faster than in the West during its period of most rapid decline, and it was much faster than in the West over the second half of the twentieth century. By the end of the century, the 26-year difference had been reduced to 10 years (although Africa lags behind the rest of the developing world).

The rapid improvement in life expectancy at birth in the third world occurred for different reasons than in the West. In the West, mortality declined paralleled socioeconomic development. In contrast, in the developing countries, mortality reductions were, in large part, due to the borrowing of Western death-control technology and public health measures. This in part was the result of the post-cold-war that saw the United States and other Western countries assist nonaligned countries with public health and mortality control in order to win their political allegiance. Whatever the political motives, the result was very successful. As in the West, life expectancy at birth was initially improved by controlling the infectious diseases to which infants and children are particularly susceptible and was accomplished by improvements in diet, sanitation, and public health. In addition, the third world was able to benefit from Western technology, such as pesticides, which played a major role in killing the mosquitoes that cause malaria, a leading cause of death in many countries. This exogenously caused reduction in mortality led to very rapid rates of population growth in most third world countries, creating what became known as the "population bomb." It also left these poor countries without a basic health (and public health) infrastructure, making them vulnerable to the effects of cutbacks in aid from foreign (Western) governments and foundations. It is in such a context that many third world countries (especially in sub-Saharan Africa but also in Southeast Asia and the Caribbean) are attempting to deal with the HIV/AIDS crisis, as well as a number of infectious diseases that were believed to have been conquered but have resurfaced through mutations.

It is difficult to predict if life expectancy differences at birth between the more and less developed countries will continue to converge. On the one hand, further increases in life expectancy in the West will be slow, resulting from improvements in the treatment and management of chronic diseases among older people. Theoretically, it would be expected that the third world could, thus, continue to catch up with West. However, new infectious diseases such as HIVS/AIDS and the re-emergence of "old" infectious diseases, sometimes in more virulent or antibiotic resistant forms, are attacking many third world countries that lack the resources to cope.

Differentials in Life Expectancy at Birth

Within populations, differences in life expectancy exist; that is, with regard to gender. Females tend to outlive males in all populations, and have lower mortality rates at all ages, starting from infancy. However, the degree to which females outlive males varies; as seen in Table 1, the difference is around three years in the less developed countries and approximately seven years in developed countries.

Another difference in life expectancy lies in social class, as assessed through occupation, income, or education. This research tends to deal with life expectancy among adults, rather than at birth. The earliest work on occupational differences was done in England using 1951 data; in 1969 the researcher Bernard Benjamin, grouping occupations into five classes, found that mortality was 18 percent higher than average in the lowest class, and 2 percent lower than average in the highest class. In the United States in 1973, Evelyn Kitagawa and Philip Hauser, using 1960 data, found that both higher education and higher income were independently associated with longer life expectancy, that is, having both high income and high education was more advantageous than just having one or the other. This was later replicated by researchers in 1993, with the additional finding that the socioeconomic difference was widening over time.

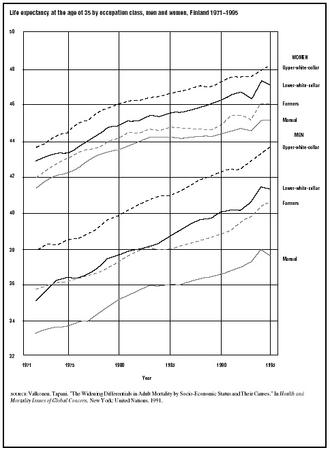

Data on social class differences in life expectancy are difficult to obtain, even in highly developed countries. A 1999 study by Tapani Valkonen contains exceptionally good data on occupational differences in life expectancy in Finland. Figure 2 shows life expectancy at age 35 for four classes of workers, by gender, for the period of 1971 to 1996. While this figure indicates that life expectancy differences by occupation show a female advantage for all occupations and that male longevity differentials are much bigger than female ones, the most important information conveyed for the purposes here is that the occupational gap in

It is not clear why socioeconomic differences in adult life expectancy are growing in Western populations. The major cause of death responsible for the widening differential is cardiovascular disease; persons of higher social classes have experienced much larger declines in death due to cardiovascular disease than persons of lower classes. It is possible that the widening is only temporary, the result of earlier declines in cardiovascular mortality among higher socioeconomic groups. Or, it may be that the widening reflects increasing polarization in health status and living conditions within Western populations. It does not appear that differences in access to health care are responsible, seeing as the trend appears in countries that both have and do not have national medical/health insurance.

Another difference in life expectancy relates to race/ethnicity. For example, in the United States, the expectation of life at birth for whites is six years higher than for African Americans. However, the difference in life expectancy at age sixty-five is less than two years. The narrowing gap with age suggests that mortality associated with younger age groups is an important factor; this inference is reinforced by high rates of homicide among African Americans, especially young males. Ethnic differences in mortality are not unique to the United States. Among countries with reliable data, it is known that the Parsis in India and the Jews in Israel have lower mortality than other ethnic groups; they share, along with whites in the United States, a place of privilege in the socioeconomic order.

See also: Aids ; Causes of Death ; Public Health

Bibliography

Benjamin, Bernard. Demographic Analysis. New York: Praeger, 1969.

Brooks, Jeffrey D. "Living Longer and Improving Health: An Obtainable Goal in Promoting Aging Well." American Behavioral Scientist 39 (1996):272–287.

Coale, Ansley J., Paul Demeny, and Barbara Vaughan. Regional Model Life Tables and Stable Populations. New York: Academic Press, 1983.

Cockerham, William C. "The Social Determinants of the Decline in Life Expectancy in Russia and Eastern Europe: A Lifestyle Explanation." Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38 (1997):117–130.

Crimmins, Eileen M. "Are Americans Healthier As Well As Longer-Lived?" Journal of Insurance Medicine 22 (1990):89–92.

Ehrich, Paul R. The Population Bomb. New York: Ballantine, 1969.

Fries, James F. "Compression of Morbidity: Life Span, Disability, and Health Care Costs." In Bruno J. Vellas, Jean-Louis Albarede, and P. J. Garry eds., Facts and Research in Gerontology, Vol. 7. New York: Springer,1993.

Fries, James F. "Compression of Morbidity." Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 61 (1983):397–419.

Guyer, Bernard, et al. "Annual Summary of Vital Statistics: Trends in the Health of Americans during the 20th Century." Pediatrics 106 (2000):1307–1318.

Hayward, Mark D., et al. "Cause of Death and Active Life Expectancy in the Older Population of the United States." Journal of Aging and Health 10 (1998):192–213.

Kaplan, George A. "Epidemiologic Observations on the Compression of Morbidity: Evidence from the Alameda County Study." Journal of Aging and Health 3 (1991):155–171.

Kitagawa, Evelyn M., and Philip M. Hauser. Differential Mortality in the United States: A Study in Socio-Economic Epidemiology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973.

Manton, Kenneth G., and Kenneth C. Land. "Active Life Expectancy Estimates for the U.S. Elderly Population: A Multidimensional Continuous Mixture Model of Functional Change Applied to Completed Cohorts, 1982–1996." Demography 37 (2000):253–265.

Manton, Kenneth G., Eric Stallard, and Larry Corder. "The Limits of Longevity and Their Implications for Health and Mortality in Developed Countries." In Health and Mortality Issues of Global Concern. New York: United Nations, 1999.

Matoso, Gary. "Russian Roulette." Modern Maturity 37, no. 5 (1994):22–28.

McKeown, Thomas. The Modern Rise of Population. London: Edward Arnold, 1976.

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2000. Hyattsville, MD: Author, 2000.

National Institute on Aging. In Search of the Secrets of Aging. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 1996.

Pappas, Gregory, et al. "The Increasing Disparity in Mortality between Socioeconomic Groups in the United States, 1960 and 1986." New England Journal of Medicine 329 (1993):103–109.

Population Reference Bureau. 2001 World Population Data Sheet. Washington, DC: Author, 2001.

Rudberg, Mark A., and Christine K. Cassel. "Are Death and Disability in Old Age Preventable?" In Bruno J. Vellas, Jean-Louis Albarede, and P. J. Garry eds., Facts and Research in Gerontology, Vol. 7. New York: Springer, 1993.

Schwartz, William B. Life without Disease: The Pursuit of Medical Utopia. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Shkolnikov, Vladimir, et al. "Causes of the Russian Mortality Crisis: Evidence and Interpretation." World Development 26 (1998):1995–2011.

United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2000 Revision. New York: Author, 2001.

Valkonen, Tapani. "The Widening Differentials in Adult Mortality by Socio-Economic Status and Their Causes." In Health and Mortality Issues of Global Concern. New York: United Nations, 1991.

Verbrugge, Lois M. "Longer Life but Worsening Health? Trends in Health and Mortality of Middle-Aged and Older Persons." Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 62 (1984):475–519.

Walford, Roy L. Maximum Life Span. New York: Norton, 1983.

Yaukey, David, and Douglas L. Anderton. Demography: The Study of Human Population. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland, 2001.

ELLEN M. GEE