Hell

Most ancient societies and religions had an idea of an afterlife judgment, especially understood as a "weighing of souls," where the gods would reward the faithful worshipers, or honor the great and mighty of society. In later times this notion of afterlife was refined more and more into a concept of the public recognition of the worth of a person's life, its moral valency. The three biblical religions— Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—all apply the notion of the afterlife judgment (and the ideas of heaven and hell which derive from this concept) as essentially a divine adjudication that assesses and pronounces on the worth of a human life. Such beliefs were to become among the most potent mechanisms of social control ever devised.

The classical Greek conception viewed Hades, the land of the dead, as a place of insubstantial shadows. The story of the "House of the Dead" in Homer's Odyssey gives a harrowing version of how even heroes are rendered into pathetic wraiths, desperately thirsting after life, waiting for the grave offerings (libations of wine or blood or the smoke of sacrifices) that their relatives would offer at their tombs. Such an afterlife was as insubstantial as smoke, a poetic evocation of the grief of loss more than anything else. There was no life or love or hope beyond the grave. By contrast the gods were immortals who feasted in an Elysian paradise, a marked contrast to the wretched fallibility of mortals whose deaths would reduce them one day, inevitably, to dust and oblivion. This resigned existentialism permeates much of classical Greek and Roman writing. It was not particularly related to the more philosophical notions, as witnessed in Plato, for example, of the soul as an immortal and godlike entity that would one day be freed when released from its bodily entrapment. However, both notions were destined to be riveted together, in one form or another, when the Christians merged the Hellenistic concepts of their cultural matrix with biblical ideas of judgment, as they elaborated the New Testament doctrine of hell.

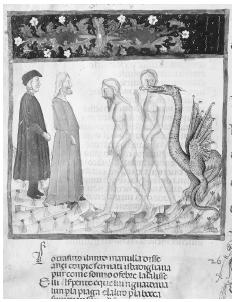

The classical descriptions of Hades were borrowed and reused by Christians as one of the first popular images for hell. The earliest iconic images of the Resurrection, in Byzantine art, depict Christ descending into Hades, breaking down the doors and liberating the souls of all those who had been consigned to imprisonment in the House of Death before his incarnation. Having broken into the realm of darkness and powerlessness, the Risen Christ is shown stretching out a hand to Adam and Eve, to lift them from their tombs, while the other righteous men and women of the days before his coming all wait in line to be taken with Christ to the glory of heaven. In the Christian era, with common allegiance being given to the idea of the immortality of the soul, Hades was now no longer a place of fading away to nonexistence, but rather a place of permanent imprisonment and sorrow. So it was that Hades made its transition toward becoming hell.

Scriptural Images of Hell As Devastation

The concept of Hades, reappropriated in this way and set to the service of the proclamation of the Resurrection victory, however, was only one form of the Christian doctrine of afterlife. Both the Egyptian Book of the Dead and the Buddhist mythology of the afterlife speak clearly enough of the afterlife as a state of judgment and the punishment of the wicked. This aspect of doctrine eventually came to be part of late Judaism, influencing both rabbinic teachings and the doctrine of Jesus, and thus coming to be a part of late classical Judaism and Christianity (not to mention Islam) to the present day. To chart the development of this stream of thought one needs to look at the prophetic view of God's justice in the world and how it came to be reassessed by the apocalyptic school.

The prophet Isaiah used the image of the fire that falls upon the wicked and established it for later use. The concept of enemy raids that inflicted destructive fires and terrible sufferings on ancient Israel was real enough to need little explanation. The invasion of enemies, however, was a major problem in the Hebrew theology of providence that was often explained by the prophets on the grounds that God only allowed infidel invaders to devastate his holy land because his covenant people had themselves been unfaithful. The image of punishing fire thus became associated in the prophetic literature with unfaithfulness as it was being corrected by God, whose anger was temporary, and who, after the devastation, would restore his people to peace and favor.

The association of ideas is seen clearly in Isaiah 66:24, which becomes a locus classicus for Jesus himself, and by this means entered into the Christian tradition as an authoritative logion, or dominical saying. In this passage the prophet speaks of a restored Jerusalem under the Messiah, when the true Israelites who have been restored by God will, in turn, go out to look upon the devastation that they have survived, and will see "those who rebelled against me, for their worm shall not die, and their fire shall not be quenched, and they shall be an abomination to all flesh." This is an image of the aftermath of devastation used as an apocalyptic sign, a theological statement about the ultimate vindication of God and his chosen people, functioning as if it were a rallying cry for the elect to retain trust in God even in times of difficulty, when the covenant hope might seem slight or politically ill-founded. From this stream of prophetic teaching the image of fires of judgment began to coalesce into a concept of hell.

Apocalyptic Ideas on God's Judgment

In the two centuries preceding the Christian era the prophetic theology of providence faltered. It was overtaken by a new mode of thought called apocalyptic, taken from the style of books that often featured a chosen prophet figure who received special revelations (apocalypses) in the heavenly court, and who then returned to announce the word of divine judgment to his contemporaries. The Book of Daniel is the one great instance of such an apocalyptic book that entered the canon of the Hebrew scriptures, although there were many other instances of such literature that were highly influential in the period between the two testaments, and which colored the Judaism of the time, as well as primitive Christianity.

The image of God's anger against the evil ways of the earth is a common feature of this genre of scripture. The divine judgment is often depicted in terms of God deciding on a definitive end to the cycle of disasters that have befallen his elect people in the course of world history. The literature depicts the forces of evil as beasts, servants of the great beast, often seen as the dark angel who rebelled against God in primeval times. The earthly beasts are, typically, the great empires that throughout history have crushed the Kingdom of God on the earth (predominantly understood as Israel). In apocalyptic imagery the great battle for good and evil is won definitively by God and his angels who then imprison the rebel forces in unbreakable bonds. An inescapable "Lake of Fire" is a common image, insofar as fire was a common biblical idiom for the devastation that accompanied divine judgment. In apocalyptic thought the definitive casting down of the evil powers into the fire of judgment is coterminous with the establishment of the glorious Kingdom of God and his saints. In this sense both heaven and hell are the biblical code for the ultimate victory of God. So it was that in apocalyptic literature the final elements of the Judeo-Christian vocabulary of hell were brought together.

The Teachings of Jesus on Gehenna

Historically understood, the teachings of Jesus belong to the genre of apocalyptic in a particular way, though are not entirely subsumed by it despite many presuppositions to the contrary in the scholarship of the twentieth century. Jesus taught the imminent approach of a definitive time of judgment by God, a time when God would purify Israel and create a new gathering of the covenant people. It was this teaching that was the original kernel of the Christian church, which saw itself as the new elect gathered around the suffering and vindicated Messiah. Jesus's own execution by the Romans (who were less than impressed by the apocalyptic vividness of his imagery of the Kingdom restored), became inextricably linked in his follower's minds with the "time of great suffering" that was customarily understood to usher in the period of God's Day of Judgment and his final vindication of the chosen people (necessarily involving the crushing of the wicked persecutors).

In his prophetic preaching, Jesus explicitly quoted Isaiah's image of the fire burning day and night, and the worm (maggot) incessantly feeding on the bloated corpses of the fallen and, to the same end as Isaiah, that when God came to vindicate Israel he would make a radical separation of the good and the wicked. The image of the judgment and separation of the good and the evil is a dominant aspect of Jesus's moral teaching and can be found in many of his parables, such as the king who judges and rewards according to the deeds of individuals in Matthew 23, or the man who harvests a field full of wheat and weeds, separating them out only at the harvest time in Matthew 13.

Jesus also used the biblical idea of Gehenna as the synopsis of what his vision of hell was like. Gehenna was the valley of Hinnom, one of the narrow defiles marking out the plateau on which Jerusalem was built. It was a biblical symbol of everything opposed to God, and as such destined to being purified when God roused himself in his judgment of the evils of the earth. It had been the place in ancient times where some of the inhabitants of Jerusalem had offered their own children in sacrifice to the god Moloch. The reforming King Josiah, as a result of "the abomination of desolation," made the valley into the place of refuseburning for the city, a place where bodies of criminals were also thrown. In Jesus' teaching (as is the case for later rabbinic literature) it thus became a symbol for the desolate state of all who fall under the judgment of God. The burning of endless fires in a stinking wasteland that symbolized human folly and destructive wickedness is, therefore, Jesus' image for the alternative to his invitation for his hearers to enter, with him, into the service of God, and into the obedience of the Kingdom of God.

Christian disciples later developed the idea of Gehenna into the more elaborated concept of hell, just as they rendered the dynamic concept of the Kingdom of God (obedience to the divine covenant) into the notion of heaven as a place for the righteous. The original point of the teachings was more dynamic, to the effect that humans have a choice to listen and respond to the prophetic call, or to ignore and oppose it. In either case they respond not merely to the prophet, but to God who sent the prophet. In the case of Jesus, those who listen and obey his teachings are described as the guests who are invited to the wedding feast; those who refuse it are compared to those who haunt the wilderness of Gehenna and have chosen the stink of death to the joy of life with God. It is a graphic image indeed, arguably having even more of an impact than the later Christian extrapolation of the eternal hellfire that developed from it.

Christian Theologians on Hell

Not all Christian theologians acceded to the gradual elision of the Hellenistic notions of Hades, and the apocalyptic imagery of the burning fires of Gehenna or the sea of flames, but certain books were quite decisive, not least the one great apocalyptic book that made its way into the canon of the New Testament, the Revelation of John, whose image of the Lake of Fire, where the dark angels were destined to be punished by God, exercised a profound hold over the imagination of the Western churches. The Byzantine and Eastern churches never afforded Revelation as much attention as did the West, and so the graphic doomsdays of the medieval period never quite entered the Eastern Orthodox consciousness to the same extent.

Some influential Greek theologians argued explicitly against the concept of an eternal hell fire that condemned reprobate sinners to an infinity of pain, on the grounds that all God's punishments are corrective, meant for the restoration of errants, and because an eternal punishment allows no possibility of repentance or correction, it would merely be vengeful, and as such unworthy of the God of infinite love. Important theologians such as Origen ( On First Principles 2.10) and his followers (Gregory Nyssa and Gregory Nazianzen, among and others) who argued this case fell under disapproval mainly because the Gospel words of Jesus described the fire of Gehenna as "eternal" even though it was a word ( aionios ) that in context did not simply mean "endless" but more to the point of "belonging to the next age."

But even with the unhappiness of the Christians with Origen's idea that hell was a doctrine intended only "for the simple who needed threats to bring them to order" ( Contra Celsum 5.15), the logic of his argument about God's majesty transcending mere vengeance, and the constant stress in the teachings of Jesus on the mercifulness of God, led to a shying away from the implications of the doctrine of an eternal hell, throughout the wider Christian tradition, even when this doctrine was generally affirmed.

Major authorities such as Augustine and John Chrysostom explained the pains of fire as symbols of the grief and loss of intimacy with God that the souls of the damned experienced. Dante developed this in the Divine Comedy with his famous conception of hell as a cold, dark place, sterile in its sense of loss. Augustine aided the development of the idea of purgatory (itself a major revision of the concept of eternal punishment). Other thinkers argued that while hell did exist (not merely as a symbol but as a real possibility of alienation from life and goodness), it was impossible to conclude that God's judgments were irreversible, for that would be to stand in judgment over God, and describe eternity simply in time-bound terms; one position being blasphemous, the other illogical.

Because of the implications, not least because of the need to affirm the ultimate mercy and goodness of God, even when acting as judge and vindicator, modern Christian theology has remained somewhat muted on the doctrine of hell, returning to it more in line with the original inspiration of the message as a graphic call to moral action. It has probably been less successful in representing the other major function of the doctrine of hell; that is, the manner in which it enshrines a major insight of Jesus and the biblical tradition, that God will defend the right of the oppressed vigorously even when the powerful of the world think that to all appearances the poor can be safely tyrannized. Originally the Christian doctrine of hell functioned as a major protecting hedge for the doctrine of God's justice and his unfailing correction of the principles of perversion in the world.

In previous generations, when hell and final judgment were the subjects of regular preaching in places of worship, the fear of hell was more regularly seen as an aspect of the approach to death by the terminally ill. In the twenty-first century, while

Because of its vivid nature, and the increasingly static graphic imagination of later Christian centuries, hell came to be associated too much with an image of God as tormentor of the souls in some eternal horror. Such a God did not correspond to the gracious "Father" described by Jesus, but like all images packaged for the religiously illiterate, the dramatic cartoon often replaces the truer conception that can be gained from the Gospels and writings of Christian saints through the centuries: that hell is a radical call to wake up and make a stand for justice and mercy, as well as a profound statement that God's holiness is perennially opposed to evil and injustice.

See also: Catholicism ; Charon and the River Styx ; Christian Death Rites, History of ; Gods and Goddesses of Life and Death ; Heaven ; Jesus ; Purgatory

Bibliography

Bernstein, Alan E. The Formation of Hell: Death and Retribution in the Ancient and Early Christian Worlds. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993.

Bromiley, Geoffrey W. "History of the Doctrine of Hell." In The Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Vol. 2. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1982.

Davidson, Clifford, and Thomas Seiler, eds. The Iconography of Hell. Kalamazoo: Western Michigan University Press, 1992.

Filoramo, Giovanni. "Hell-Hades." In Angelo Di Berardino ed., Encyclopedia of the Early Church, Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Fudge, Edward. The Fire That Consumes: A Biblical and Historical Study of Final Punishment. Fallbrook, CA: Verdict Publications, 1982.

Gardner, Eileen. Medieval Visions of Heaven and Hell: A Sourcebook. New York: Garland, 1993.

Moore, David George. The Battle for Hell: A Survey and Evaluation of Evangelicals' Growing Attraction to the Doctrine of Annihilationism. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1995.

Turner, Alice K. The History of Hell. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1993.

Van Scott, Miriam. The Encyclopedia of Hell. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998.

J. A. McGUCKIN

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: