Purgatory

From the third century onward, Christian theologians developed a theory of psychic postdeath purification on the basis of the words of St. Paul: "Fire shall try every person's work." He continues by saying that those who have built their lives upon shoddy foundations "shall be saved, yet saved through fire" (1 Cor. 3:11–15). Paul's was a doctrine of postdeath purification that was shared with late Judaism and early rabbinic thought. From the beginning of their organized existence, therefore, both the synagogue and the early Christian church prayed extensively for their dead, and many of the most ancient prayers to this effect are still found in the liturgies of the Greek and Latin churches.

Several early theologians reflected on the obscurities of the primitive Christian teaching on the state of the soul after death and deduced that between the death of the individual and the final judgment at the end of time there would be an intermediate state. During this state the souls of the dead inhabited a place where, according to their deeds, they were either happy or wretched. Those souls who required purification of their past lives would experience the purifying fire (in Latin purgatorium ) more drastically than those who were more advanced in holiness before their death. The Greek theologians generally regarded the posthumous purification by fire in the "spiritual" or symbolic sense of psychic transfiguration into a higher condition. Clement and Origen of Alexandria had envisaged that the soul of the departed would be made to learn all the things it had refused to learn on the earth through the strenuous ministrations of correcting angels until it had been purified enough to ascend closer to God. The fourth-century teacher Gregory of Nyssa expressed the idea more generically: "We must either be purified in the present life by prayer and the love of wisdom ( philosophias ) or, after our departure from this world, in the furnace of the purifying fire." And Gregory of Nazianzus, his contemporary, writes in his poetry of the "fearful river of fire" that will purify the sinner after death.

The idea of purgatorium as a place of after-death purification distinct from the finality of the place of the elect and the damned (heaven or hell) that would be determined by God only on Judgment Day was put forward as a learned opinion by leading Western theologians, particularly Jerome, Augustine, and Gregory the Great. These thinkers seemed to wish more than the Easterners to bring some systematic order into the diffuse doctrine of the afterlife and judgment. It was Pope Gregory in the seventh century who elevated the opinion of the earlier thinkers into a more or less formulated doctrine: "Purgatorial fire will cleanse every elect soul before they come into the Last Judgement." So began the divergent thought that developed over the course of centuries between the Byzantines and Latins.

The Eastern Christian world retained a simpler doctrine of the afterlife that maintained that the souls of the elect, even those who were not particularly holy, would be retained in "a place of light, a place of refreshment, a place from which all sorrow and sighing have been banished." This view reflected the statement in Revelation 14:13 that "those who die in the Lord rest from their labors." In short, the state of afterlife as it was envisaged in the Eastern church was generally a happy and restful condition in which the departed souls of the faithful were not divorced from God, but waited on Judgment Day with hopeful anticipation, as the time when they would be admitted to a transfigured and paradisial condition in proximity to God.

The Latin church, on the other hand, developed its doctrine of purgatory with a more marked stress on that state of painful purification that would attend the souls of all those who had not reached a state of purity before their death.

In the tradition of both churches, the state of the souls after death called out to the living to assist them in prayers, both public and private, so that God would show them mercy. In the tenth century, under the influence of Odilo of Cluny, the Feast of All Souls (November 2) was established in the Western calendar as a time when the living prayed for the release from sufferings of all departed Christians. The popularity of this feast helped to fix the idea of purgatory in the religious imagination of Latin Christians. After the twelfth century, Western theology further rationalized the state and purpose of purgatory in arguing that it was a cleansing by fire of the lesser sins and faults committed by Christians (venial sins), and the payment of the debt of "temporal punishment," which medieval theologians taught was still owed by those who had committed grave offenses (mortal sins) even though the penalty of such sins (condemnation to an eternity in hell) had been remitted by God before death. The later rationalization for purgatory, therefore, stood in close relation to the highly developed Western church's penitential theory, as the latter had devolved from feudal ideas of penal debt and remission. The theological tendency is best seen in the work of the scholastic theologian Anselm, who reflects on the nature of eternal penalties incurred by mortals who offend against the prescripts of the deity, in his influential study of the atonement Cur Deus Homo (On Why God was Made Man), published in 1098.

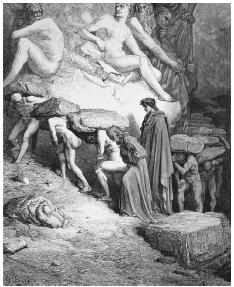

Purgatory, as it developed in the West through the later Middle Ages, became more and more of a dismal idea, linked to the understanding of redemption as a penal substitutionary sacrifice, and increasingly distanced from the early Christian notion that the redemption represented God's glorious victory given as a gift to liberate the world. The medieval obsession with the state of the souls after death led to a flourishing of legends and popular narratives of the sufferings of the souls in purgatory. They were, in a sense, the prelude to the greatest medieval work of graphic imagination relating to the subject, Dante's Purgatory, the second book of the Divine Comedy. Mystics such as Catherine of Genoa also made it a central theme of their visionary teachings, further fixing the idea in the Western mind. In the medieval Latin church the desire to assist the departed souls in their time of sorrow led to a thriving demand for masses and intercessions for the dead, and for "indulgences," which were held to lessen the time of suffering that the souls in purgatory would be required to undergo. This led soon enough to the concept of purgatory being one of the early points of contention in the great religious crisis known subsequently as the Reformation.

Protestant theologians rejected the doctrine of purgatory as one of their first public departures from medieval theological speculation, and the English church censured the "Romish doctrine of Purgatory" outright in its Article 22. The Orthodox churches had much earlier censured the whole idea when ecumenical union was being contemplated in the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. On each occasion, the Latin Church defended its position in conciliar statements (the Council of Lyons in 1274 and the Council of Florence in 1439). The rejection of the idea by the Reformation teachers led to its defense once again in the sixteenth-century Council of Trent, which led to renewed focus on the idea of purgatory as a distinguishing mark of the authority of the Roman Catholic Church in the domain of defining dogmas not clearly distinguished in the scriptural accounts.

As an idea it lives on in Dante's writings, and in dramatic poems such as John Henry Newman's nineteenth-century "Dream of Gerontius." As a religious factor it is still very much alive in Western Catholicism in the celebration of various Feasts of the Dead, and in the liturgical commemorations of the departed on November 2. Modern Roman Catholic theology, after Trent, has clearly moved away from emphasizing the purifying pains of purgatorial fire and instead highlights the need for the living to commemorate the dead who have preceded them.

See also: Afterlife in Cross-Cultural Perspective ; Heaven ; Hell

Bibliography

Atwell, Robert. "From Augustine to Gregory the Great: An Evaluation of the Emergence of the Doctrine of Purgatory." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 38 (1987):173–186.

d'E Jesse, Eustace T. Prayers for the Departed, Purgatory, Pardons, Invocations of Saints, Images, Relics: Some Remarks and Notes on the 22nd Article of Religion. London: Skeffington & Sons, 1900.

Hubert, Father. The Mystery of Purgatory. Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1975.

Le Goff, Jacques The Birth of Purgatory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Ombres, Robert. The Theology of Purgatory. Cork: Merces Press, 1979.

J. A. McGUCKIN

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: