Children and Their Rights in Life and Death Situations

In 2003 approximately 55,000 children and teenagers in the United States will die. Accidents and homicide cause the most deaths, and chronic illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, and congenital abnormalities are the next greatest cause. The loss of a child or adolescent is life-altering for the family, friends, community members, and health care providers, regardless of the cause of death. Most children and adolescents who have a terminal illness are capable of expressing their preferences about how they will die. These preferences have not always been solicited or honored by the adults involved in their care.

Defining the End of Life in Pediatrics

The term end-of-life care for children and adolescents has a more global meaning than the commonly used terms terminal care, hospice care, and palliative care. Rather than defining a specific time period, "end-of-life care" denotes a transition in the primary goal of care from "curative" (in cases of disease) or "life sustaining" (in cases of trauma) to symptom management (the minimization or prevention of suffering) and on psychological and spiritual support for the dying child or adolescent and for the family. To provide this kind of care to fatally ill children and adolescents and to their family members, health care providers must focus on the individual patient's values and preferences in light of the family's values and preferences. Hospice care is considered to be end-of-life care, but it usually includes the expectation that the child's life will end in six months or less. Palliative care is defined variously among health care providers. Some characterize it as "a focus on symptom control and quality of life throughout a life-threatening illness, from diagnosis to cure or death." Others define it as "management of the symptoms of patients whose disease is active and far advanced and for whom cure is no longer an option." This entry uses the term end-of-life care in its broader sense.

Historical Evolution of End-of-Life Care for Children and Adolescents

Today, as in the past, the values and preferences of children who are less than eighteen years of age have little or no legal standing in health care decision making. Some professionals doubt that children have the ability to adequately understand their health conditions and treatment options and therefore consider children to be legally incompetent to make such decisions. Instead, parents or guardians are designated to make treatment choices in the best interests of the minor child and to give consent for the child's medical treatment.

Since the 1980s clinicians and researchers have begun to challenge the assumption that children and adolescents cannot understand their serious medical conditions and their treatment options. Clinical anecdotes and case studies indicate that children as young as five years of age who have been chronically and seriously ill have a more mature understanding of illness and dying than their healthy peers. Still other case reports convey the ability of children and adolescents to make an informed choice between treatment options.

Researchers have documented children's preference to be informed about and involved in decisions regarding treatment, including decisions about their end-of-life care. Although there have been only a few studies about ill children's preferences for involvement in treatment decision making, a growing number of professional associations have published care guidelines and policy statements urging that parents and their children be included in such decision making. In fact, several Canadian provinces have approved legislative rulings supporting the involvement of adolescents in medical decision making. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children be included in clinical decision making "to the extent of their capacity." At the federal level, the National Commission for Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research identified the age of seven years as a reasonable minimum age at which assent of some type should be sought from a child for participation in a research protocol. According to the commission's findings, a child or adolescent at the end of life, as at other times, should be informed about the purpose of the research and given the option of dissent. In such cases, researchers should approach a child or adolescent about a study while the child is still able to give assent or to decline to participate. If this is not possible, a proxy (parent or guardian) must decide in the child's best interest.

Although parents or guardians generally retain the legal right to make final care decisions for their children, it is respectful of a child's dignity to engage the child in discussions about his or her wishes and goals. In one study, parents who were interviewed after the death of their child described finding comfort in the fact that they had made endof-life treatment decisions that their child had preferred or that they felt certain their child would have preferred. In sum, children and adolescents nearing the end of life benefit from age-appropriate explanations of their disease, treatment options, and prognosis, and from having their preferences about their care respected as much as possible.

Talking about Dying with Children or Adolescents

One of the most difficult aspects of caring for seriously ill children or adolescents is acknowledging that survival is no longer possible. The family looks to health care providers for information about the likelihood of their child's survival. When it is medically clear that a child or adolescent will not survive, decisions must be made about what information to share with the parents or guardians and how and when to share that information. Typically, a team of professionals is involved in the child's care. Before approaching the family, members of the team first discuss the child's situation and reach a consensus about the certainty of the child's death. The team members then agree upon the words that will be used to explain this situation to the parents and the child, so that the same words can be used by all members of the team in their interactions with the family. Careful documentation in the child's medical record of team members' discussions with the patient and family, including the specific terms used, is important to ensure that all team members are equally well informed so that their care interactions with the child and family are consistent. Regrettably, a study by Devictor and colleagues of decision-making in French pediatric intensive care units reported in 2001 that although a specific team meeting had been convened in 80 percent of the 264 consecutive children's deaths to discuss whether to forgo life-sustaining treatment, the meeting and the decision had been documented in only 16 percent of the cases in the patient's medical record.

The greatest impediment to decision making at the end of life is the lingering uncertainty about the inevitability of a child's death. Such uncertainty, if it continues, does not allow time for a coordinated, thoughtful approach to helping the parents and, when possible, the child to prepare for the child's dying and death. Depending on the circumstances, such preparation may have to be done quickly or may be done gradually. The child's medical status, the parent's level of awareness, and the clinician's certainty of the child's prognosis are all factors in how much time will be available to prepare for the

Although there is little research-based information about end-of-life decision making and family preparation, evidence-based guidelines for decision making are available. While some studies and clinical reports support the inclusion of adolescents in end-of-life discussions and decisions, there are no studies that examine the role of the younger child. Clinical reports do, however, support the idea that younger children are very much aware of their impending deaths, whether or not they are directly included in conversations about their prognosis and care.

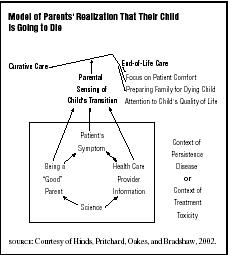

Health care professionals uphold that continuous communication be maintained between the parents and the health care team about the status of the dying child. Parents may react to their child's terminal status in various ways, including denial. If parents appear to be in denial, it is important to ensure that they have been clearly told of their child's prognosis. In 2000 the researcher Joanne Wolfe and colleagues reported that some parents whose child had died of cancer realized after the death that they had perceived that their child was going to die significantly later than the health care team had known. Parents and other family members often vacillate between different emotional responses and seek opportunities to discuss and rediscuss their child's situation with the health care team.

Parents will often want to know when their child will die and exactly what will occur. Although it is difficult to predict when a child will die, useful information can be given about symptoms the child is likely to experience, such as breathing changes, decreasing appetite, and decreasing energy. Most importantly, parents will need to be assured that their child will be kept comfortable and that members of the health care team will be readily available to the child and the family.

Siblings may exhibit a variety of responses to the impending death of a brother or sister. These responses will be influenced by the sibling's age and developmental maturity, the length of time the dying child has been ill, and the extent to which the sibling has been involved in the patient's care. Siblings need to be told that it is not their fault that the brother or sister is dying. Siblings have indicated their need to be with the dying sibling and, if possible, to be involved in the sibling's daily care; if these are not possible, they need at least to be informed regularly about the status of their dying sibling.

Keeping the Dying Child Comfortable: Symptom Management Strategies

Children who have experienced suffering may fear pain, suffocation, or other symptoms even more than death itself. Anticipating and responding to these fears and preventing suffering is the core of end-of-life care. Families need assurance that their child will be kept as comfortable as possible, and clinicians need to feel empowered to provide care that is both competent and compassionate. As the illness progresses, treatment designed to minimize suffering should be given as intensively as curative treatments. If they are not, parents, clinicians, and other caregivers will long be haunted by memories of a difficult death.

The process of dying varies among children with chronic illness. Some children have relatively symptom-free periods, then experience acute exacerbation of symptoms and a gradual decline in activity and alertness. Other children remain fully alert until the final hours. Research specific to children dying of various illnesses has shown that most patients suffer "a lot" or "a great deal" from at least one symptom, such as pain, dyspnea, nausea, or fatigue, in their last month of life.

Although end-of-life care focuses on minimizing the patient's suffering rather than on prolonging life, certain supportive measures (such as red blood cell and platelet transfusions and nutritional support) are often continued longer in children than in adults with terminal illnesses. The hope, even the expectation, is that this support will improve the child's quality of life by preventing or minimizing adverse events such as bleeding. Careful discussion with the family is important to ensure that they understand that such interventions will at some point probably no longer be the best options. Discussions about the child's and family's definition of well-being, a "good" death, their religious and cultural beliefs, and their acceptance of the dying process help to clarify their preferences for or against specific palliative interventions. For example, one family may choose to continue blood product support to control their child's shortness of breath, whereas others may opt against this intervention to avoid causing the child the additional discomfort from trips to the clinic or hospital. Health care professionals should honor each family's choices about their child's care.

It is crucial that health care professionals fully appreciate the complexities of parental involvement in decisions about when to stop life-prolonging treatment. Parental involvement can sometimes result in the pursuit of aggressive treatment until death is imminent. In such cases, it becomes even more important that symptom management be central in the planning and delivery of the child's care. Conventional pharmacological and nonpharmacological methods of symptom control, or more invasive measures such as radiation for bone pain or thoracentesis for dyspnea, can improve the child's comfort and thus improve the child's and family's quality of life. As the focus of care shifts from that of cure to comfort, the child's team of caregivers should be aware of the family's and, when possible, the child's wishes regarding the extent of interventions.

Not all symptoms can be completely eliminated; suffering, however, can always be reduced. Suffering is most effectively reduced when parents and clinicians work together to identify and treat the child's symptoms and are in agreement about the goals of these efforts. Consultation by experts in palliative care and symptom management early in the course of the child's treatment is likely to increase the effectiveness of symptom control.

Accurate assessment of symptoms is crucial. Health care professionals suggest that caretakers ask the child directly, "What bothers you the most?" to assure that treatment directly addresses the child's needs. Successful management of a symptom may be confusing to the child and his parents, especially if the symptom disappears. It is important that they understand that although the suffering has been eliminated, the tumor or the illness has not.

Although it is not always research-based, valuable information is available about the pharmacological management of symptoms of the dying child. A general principle is to administer appropriate medications by the least invasive route; often, pharmacological interventions can be combined with practical cognitive, behavioral, physical, and supportive therapies.

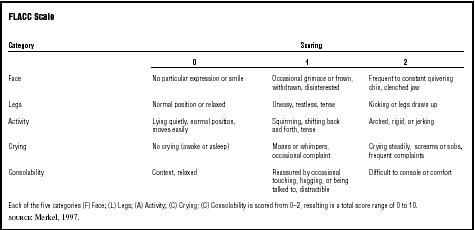

Pain. A dying child can experience severe pain; vigilant monitoring of the child's condition and regular assessment of pain intensity is essential. When the child is able to describe the intensity of pain, the child's self-report is the preferred indicator. When a child is unable to indicate the intensity of the pain, someone who is very familiar with the child's behavior must be relied upon to estimate the pain. Observational scales, such as the FLACC, may be useful in determining the intensity of a child's pain (see Table 1).

Children in pain can find relief from orally administered analgesics given on a fixed schedule. Sustained-release (long-acting) medications can provide extended relief in some situations and can

| FLACC Scale | |||

| Category | Scoring | ||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Face | No particular expression or smile | Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn, disinterested | Frequent to constant quivering chin, clenched jaw |

| Legs | Normal position or relaxed | Uneasy, restless, tense | Kicking or legs drawn up |

| Activity | Lying quietly, normal position, moves easily | Squirming, shifting back and forth, tense | Arched, rigid, or jerking |

| Crying | No crying (awake or asleep) | Moans or whimpers, occasional complaint | Crying steadily, screams or sobs, frequent complaints |

| Consolability | Content, relaxed | Reassured by occasional touching, hugging, or being talked to, distractible | Difficult to console or comfort |

| Each of the five categories (F) Face; (L) Legs; (A) Activity; (C) Crying; (C) Consolability is scored from 0–2, resulting in a total score range of 0 to 10. | |||

| SOURCE : Merkel, 1997. | |||

be more convenient for patients and their families. Because the dose increments of commercially available analgesics are based on the needs of adults and long-acting medications cannot be subdivided, the smaller dose increments needed for children may constrain use of sustained-release formulations (see Table 2, which offers guidelines for determining initial dosages for children). The initial dosages for opioids are based on initial dosages for adults not previously treated with opioids. The appropriate dosage is the dosage that effectively relieves the pain. One review completed by Collins and colleagues in 1995 reported that terminally ill children required a range of 3.8 to 518 mg/kg/hr of morphine or its equivalent.

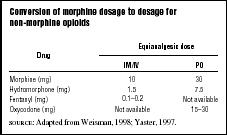

The appropriate treatment for pain depends on the type and source of the pain. Continuous clinical judgment is needed, especially when potentially interacting medications are given concurrently. If morphine is contraindicated or if the patient experiences unacceptable side effects, clinicians can use a conversion table (see Table 3) to calculate the equivalent dose of a different opioid. Approximately 50 to 75 percent of the morphine-equivalent dose should be used initially. It is usually not necessary to start at 100 percent of the equianalgesic dose to achieve adequate pain control. Constipation, sedation, and pruritus can occur as side effects of opioids. Table 2 lists medications that can prevent or relieve these symptoms. The fear of addiction is a significant barrier to effective pain control, even in dying children. Family and patient fears should be actively addressed by the health care team.

Dyspnea and excess secretions. As the child's death approaches, respiratory symptoms may be distressing for both the child and the family. Anemia, generalized weakness, or tumor compression of the airways will further exacerbate respiratory symptoms. Air hunger is the extreme form of dyspnea, in which patients perceive that they cannot control their breathlessness. When a child becomes air hungry, the family may panic. Dyspnea must be treated as aggressively as pain, often with opioids. Although some medical practitioners believe that opioids should not be used to control air hunger at the end of life because they fear the opioids may cause respiratory depression, other medical professionals believe this is untrue and that the optimal dose of opioid is the dose that effectively relieves the dyspnea.

The management of dyspnea is the same in children and adults: positioning in an upright position, using a fan to circulate air, performing gentle oral-pharyngeal suctioning as needed, and supplementary oxygen for comfort. The child may have copious, thin, or thick secretions. Pharmacological options for managing respiratory symptoms are

| Pharmacological approach to symptoms at the end-of-life of children | |||

| Symptom | Medication | Route: Starting dose/schedule | Additional comments |

| Mild to moderate generalized pain |

Acetaminophen

(Tylenol) |

PO: 10 to 15 mg/kg q 4 hrs PR: 20 to 25 mg/kg q 4 hrs | Maximum 75 mg/kg/day or 4000 mg/day; limited anti-inflammatory effect |

|

Ibuprofin

(Motrin) |

PO: 5 to 10 mg/kg q 6 to 8 hrs | Maximum 40 mg/kg/dose or 3200 mg/day; may cause renal, gastrointestinal toxicity; interferes with platelet function | |

|

Choline Mg

Trisalicylate (Trilisate) |

PO: 10 to 15 mg/kg q 8 to 12 hrs | Maximum 60 mg/kg/day or 3000 mg/day; may cause renal, gastrointestinal toxicity; less inhibition of platelet function than other NSAIDs | |

|

Ketoralac

(Toradol) |

IV: 0.5 mg/kg q 6 hrs | Limit use to 48 to 72 hours | |

| Mild to severe pain | Oxycodone | PO: initial dose of 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg q 3 to 4 hrs (no maximum dose) | Available in a long-acting formulations (oxycontin) |

| Morphine (for other opioids see conversion chart; usual dosages are converted to dose already established with the morphine) |

All doses as initial doses (no maximum dose with triation)

PO/SL: 0.15 to 0.3 mg/kg q 2 to 4 hrs IV/SC intermittent: 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg q 2 to 4 hrs IV continuous: initial bolus of 0.05 mg/kg followed by an infusion of 0.01 to 0.04 mg/kg/hr IV PCA: 0.02 mg/kg with boluses of 0.02 mg/kg q 15 to 20 min. Titrate to desired effect |

PO: available in several long-acting formulations (Oramorph; MS Contin) For severe acute pain, IV: 0.05 mg/kg boluses every 5 to 10 minutes until pain is controlled. Once controlled, begin continuous infusion and bolus as indicated on the left. | |

|

Gabapentin

(Neurontin) for neuropathic pain |

PO: 5 mg/kg or 100 mg BID | Takes 3–5 days for effect; increase dose gradually to 3600 mg/day | |

|

Amitriptyline

(Elavil) for neuropathic pain |

PO: 0.2 mg/kg/night | Takes 3–5 days for effect; increase by doubling dose every 3 to 5 days to a maximum of 1 mg/kg/dose; use with caution with cardiac conduction disorders | |

| Bone pain | Prednisone | PO: 0.5 to 2 mg/kg/day for children > 1 year, 5 mg/day | Avoid during systemic or serious infection |

| Dyspnea | Morphine |

PO: 0.1 to 0.3 mg/kg q 4 hrs

IV intermittent: 0.1 mg/kg q 2 to 4 hrs |

|

| For secretions contributing to distress |

Glycopyrrolate

(Robinul) |

PO: 40 to 100 mg/kg 3 to 4 times/day

IV: 4 to 10 mg/kg every 3 to 4 hrs |

|

| Nausea |

Promethazine

(Phenergan) |

IV or PO: 0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg q 4 to 6 hours | Maximum 25 mg/dose; may have extrapyramidal side effects |

|

Odansetron

(Zofran) |

IV: 0.15 mg/kg q 4 hrs

PO: 0.2 mg/kg q 4 hrs |

Maximum 8 mg/dose | |

| *If caused by increased intracranial pressure |

Lorazepam

(Ativan) |

PO/IV: 0.03 to 0.2 mg/kg q 4 to 6 hrs | IV: Titrate to a maximum 2 mg/dose |

| *If caused by anorexia | Dexamethasone | IV/PO: 1 to 2 mg/kg initially; then 1 to 1.5 mg/kg/day divided q 6 hrs | Maximum dose of 16 mg/day |

| *If caused by reflux |

Metoclopramide

(Reglan) |

IV: 1 to 2 mg/kg q 2 to 4 hrs | Maximum 50 mg/dose; may cause paradoxical response; may have extrapyramidal side effects |

| Anxiety or seizures |

Lorazepam

(Ativan) |

PO/IV: 0.03 to 0.2 mg/kg q 4 to 6 hrs | IV: Titrate to a maximum 2 mg/dose |

|

Midazolam

(Versed) |

IV/SC: 0.025 to 0.05 mg/kg q 2 to 4 hrs

PO: 0.5 to 0.75 mg/kg PR: 0.3 to 1 mg/kg |

Titrate to a maximum of 20 mg | |

| Anxiety or seizures |

Diazepam

(Valium) |

IV: 0.02 to 0.1 mg/kg q 6 to 8 hrs with maximum administration rate

of 5 mg/kg

PR: use IV solution 0.2 mg/kg |

Maximum dose of 10 mg |

|

Phenobarbital

(for seizures) |

For status epilepticus, IV: 10 to 20 mg/kg until seizure is resolved | Maintenance treatment IV/PO: 3 to 5 mg/kg/day q 12 hrs | |

|

Phenytoin

(Dilantin) for seizures |

IV: 15 to 20 mg/kg as loading dose (maximum rate of 1 to 3 mg/kg/min or 25 mg/min | Maintenance treatment IV/PO: 5 to 10 mg/kg/day | |

| [CONTINUED] | |||

![TABLE 2 [CONTINUED]](../images/medd_01_img0035.jpg)

| Pharmacological approach to symptoms at the end-of-life of children [CONTINUED] | |||

| Symptom | Medication | Route: Starting dose/schedule | Additional comments |

| For sedation related to opioids | Methylphenidate (Ritalin) | PO: 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg in morning and early afternoon | Maximum dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day |

| Dextroamphetamine | PO: 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg in morning and early afternoon | Maximum dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day | |

| Pruritus | Diphenhydramine (Benedryl) | PO/IV: 0.5 to 1 mg/kg q 6 hrs | Maximum dose of 50 mg/dose |

| Constipation | Senna (Senekot) | PO: 10 to 20 mg/kg/dose or 1 tablet BID | |

| Bisacodyl | PO: 6–12 years, 1 table q day > 12 years, 2 tablets q day | ||

| Docusate | PO divided into 4 doses: < 3 years, 10–40 mg 3–6 years, 20–60 mg 6–12 years, 40–120 mg > 12 years, 50–300 mg | Stool softener, not a laxative | |

| Pericolace | 1 capsule BID | Will help prevent opioid-related constipation if given for every 30 mg of oral morphine per 12-hour period | |

| PO = by mouth; SL = sublingual; PR = per rectum; IV = intravenous route; SC = subcutaneous route; PCA = patient controlled analgesia pump; q = every; NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |||

| SOURCE: Adapted from McGrath, Patricia A., 1998; St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, 2001; Weisman, Steven J., 1998; World Health Organization, 1998; Yaster, M., E. Krane, R. Kaplan, C. Cote, and D. Lappe, 1997. | |||

also outlined in Table 2. Anxiolytic agents are often needed to relieve the significant anxiety that can accompany dyspnea.

Nausea. Multiple effective options are available for the management of nausea and vomiting in dying children. Unrelieved nausea can make other symptoms worse, such as pain and anxiety (see Table 2).

Anxiety and seizures. Restlessness, agitation, and sleep disturbances may be caused by hypoxia and metabolic abnormalities related to renal and hepatic impairment. A supportive environment may be the most effective strategy to counter these symptoms. Cautious use of anxiolytics may also be helpful (see Table 2). Although dying children rarely have seizures, they are upsetting for the child and his caregivers. Strategies to manage seizures are listed in Table 2.

Fatigue. Dying children commonly experience fatigue, which can result from illness, anemia, or inadequate calorie intake. Fatigue may be lessened if care activities are grouped and completed during the same time period. The use of blood products to reduce fatigue should be carefully considered by the family and health care team.

| Conversion of morphine dosage to dosage for non-morphine opioids | ||

| Equianalgesic dose | ||

| Drug | IM/IV | PO |

| Morphine (mg) | 10 | 30 |

| Hydromorphone (mg) | 1.5 | 7.5 |

| Fentanyl (mg) | 0.1–0.2 | Not available |

| Oxycodone (mg) | Not available | 15–30 |

| SOURCE : Adapted from Weisman, 1998; Yaster, 1997. | ||

Choosing a Hospice

Ensuring the availability of appropriate home care services for children who are dying has become more challenging in this era of managed care, with its decreasing length of hospital stays, declining reimbursement, and restricted provider networks. Health care providers and parents can call Hospice Link at 1-800-331-1620 to locate the nearest hospice. Callers should ask specific questions in order to choose the best agency to use for a child; for example, "Does your agency . . ."

- • Have a state license? Is your agency certified or accredited?

- •Take care of children? What percentage of patients are less than twelve years of age? From twelve to eighteen years?

- • Have certified pediatric hospice nurses?

- • Have a staff person on call twenty-four hours a day who is familiar with caring for dying children and their families?

- • Require competency assessments of staff for caring for a child with _______ (specific disease of the child); certain health care equipment, etc.?

- • Require a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order?

- •Provide state-of-the art symptom management geared to children? Please describe.

- • Not provide certain interventions such as parenteral nutrition or platelet transfusions?

- • Commit to providing regular feedback from the referring agency/provider to promote continuity of care?

Visiting the Web

The increasing number of web sites related to endof-life care for children makes additional information available to both health care providers and families. Visiting a web site that describes a model hospice may be useful in selecting one that is within the family's geographic location ( www.canuckplace.com/about/mission.html ). Information about hospice standards of care can be found at www.hospicenet.org / and www.americanhospice.org/ahfdb.htm (those associated with American Hospice Foundation).

See also: Children ; Children AND Adolescents' Understanding OF Death ; Children, Caring For When Life-Threatened OR Dying ; End- OF -Life Issues ; Informed Consent

Bibliography

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics. "Guidelines on Foregoing Life-Sustaining Medical Treatment." Pediatrics 93, no. 3 (1994):532–536.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics. "Informed Consent, Parental Permission, and Assent in Pediatric Practice (RE9510)." Pediatrics 95, no. 2 (1995):314–317.

American Nurses Association, Task Force on the Nurse's Role in End-of-Life Decisions. Compendium of Position Statements on the Nurse's Role in End-of-Life Decisions. Washington, DC: Author, 1991.

Angst, D.B., and Janet A. Deatrick. "Involvement in Health Care Decision: Parents and Children with Chronic Illness." Journal of Family Nursing 2, no. 2 (1996): 174–194.

Awong, Linda. "Ethical Dilemmas: When an Adolescent Wants to Forgo Therapy." American Journal of Nursing 98, no. 7 (1998):67–68.

Buchanan, Allen, and Dan Brock. Deciding for Others: The Ethics of Surrogate Decision Making. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Children's International Project on Palliative/Hospice Services (CHIPPS). Compendium of Pediatric Palliative Care. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2000.

Collins John J., Holcomb E. Grier, Hannah C. Kinney, and C. B. Berde. "Control of Severe Pain in Children with Terminal Malignancy." Journal of Pediatrics 126, no. 4 (1995):653–657.

Devictor, Denis, Duc Tinh Nguyen, and the Groupe Francophone de Reanimation et d'Urgences Pediatriques. "Forgoing Life-Sustaining Treatments: How the Decision Is Made in French Pediatric Intensive Care Units." Critical Care Medicine 29 no. 7 (2001):1356–1359.

Fraeger, G. "Palliative Care and Terminal Care of Children." Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 6, no. 4 (1997):889–908.

Goldman, Ann. "Life Threatening Illness and Symptom Control in Children." In D. Doyle, G. Hanks, and N. MacDonald eds., Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Goldman, Ann, and R. Burne. "Symptom Management." In Anne Goldman ed., Care of the Dying Child. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Hanks, Geoffry, Derek Doyle, and Neil MacDonald. "Introduction." Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Hinds, Pamela S., and J. Martin. "Hopefulness and the Self-Sustaining Process in Adolescents with Cancer." Nursing Research 37, no. 6 (1988):336–340.

Hinds, Pamela S., Linda Oakes, and Wayne Furman. "Endof-Life Decision-Making in Pediatric Oncology." In B. Ferrell and N. Coyle eds., Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing Care. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

James, Linda S., and Barbra Johnson. "The Needs of Pediatric Oncology Patients During the Palliative Care Phase." Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing 14, no. 2 (1997):83–95.

Kluge, Eike Henner. "Informed Consent By Children: The New Reality." Canadian Medical Association Journal 152, no. 9 (1995):1495–1497.

Levetown, Marcia. "Treatment of Symptoms Other Than Pain in Pediatric Palliative Care." In Russell Portenoy and Ednorda Bruera eds., Topics in Palliative Care, Vol. 3. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Lewis Catherine, et al. "Patient, Parent, and Physician Perspectives on Pediatric Oncology Rounds." Journal of Pediatrics 112, no. 3 (1988):378–384.

Lindquist Ruth Ann, et al. "Determining AACN's Research Priorities for the 90's." American Journal of Critical Care 2 (1993):110–117.

Martinson, Idu M. "Caring for the Dying Child." Nursing Clinics of North America 14, no. 3 (1979):467–474.

McCabe, Mary A., et al. "Implications of the Patient Self-Determination Act: Guidelines for Involving Adolescents in Medical Decision-Making." Journal of Adolescent Health 19, no. 5 (1996):319–324.

McGrath, Patricia A. "Pain Control." In D. Doyle, G. Hanks, and N. MacDonald eds., Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Merkel, Sandra, et al. "The FLACC: A Behavioral Scale for Scoring Postoperative Pain in Young Children." Pediatric Nursing 23, no. 3 (1997):293–297.

Nitschke, Ruprecht, et al. "Therapeutic Choices Made By Patients with End-Stage Cancer." Journal of Pediatrics 10, no. 3 (1982):471–476.

Ross, Lainie Friedman. "Health Care Decision Making by Children: Is It in Their Best Interest?" Hastings Center Report 27, no. 6 (1997):41–45.

Rushton, Cynthia, and M. Lynch. "Dealing with Advance Directives for Critically Ill Adolescents." Critical Care Nurse 12 (1992):31–37.

Sahler, Olle Jane, et al. "Medical Education about End-of-Life Care in the Pediatric Setting: Principles, Challenges, and Opportunities." Pediatrics 105, no. 3 (2000):575–584.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. Guidelines for Pharmacological Pain Management.2001.

Sumner, Lizabeth. "Pediatric Care: The Hospice Perspective." In B. Ferrell and N. Coyle eds., Textbook of Palliative Nursing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Vachon, Mary. "The Nurse's Role: The World of Palliative Care." In B. Ferrell and N. Coyle eds., Textbook of Palliative Nursing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Weir, Robert F., and C. Peters. "Affirming the Decision Adolescents Make about Life And Death." Hastings Center Report 27, no. 6 (1997):29–40.

Weisman, Steven. "Supportive Care in Children with Cancer." In A. Berger, R. Portenoy, and D. Weismann eds., Principles and Practice of Supportive Oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven, 1998.

Wolfe, Joanne, et al. "Symptoms and Suffering at the End of Life in Children with Cancer." New England Journal of Medicine 342, no. 5 (2000):326–333.

Wong, Donna, et al. Whaley and Wong's Nursing Care of Infants and Children, 6th edition. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1999.

World Health Organization. Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care in Children. Geneva: Author, 1998.

Yaster, Myron, et al. Pediatric Pain Management and Sedation Handbook. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1997.

Internet Resources

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. "Policy Statement: Palliative Care for Children." In the American Academy of Pediatrics [web site]. Available from www.aap.org/policy/re0007.html .

PAMELA S. HINDS GLENNA BRADSHAW LINDA L. OAKES MICHELE PRITCHARD

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: