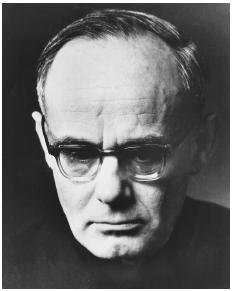

Rahner, Karl

The Jesuit priest Karl Rahner is widely regarded to have been one of the leading Catholic theologians of the twentieth century. Rahner's early writings on death were published at a time when academic theology gave little serious consideration to the topic. Less sophisticated believers generally assumed that they knew what death was, and quickly moved on to mythological conjectures about the afterlife. Rahner sought to illuminate death's religious and theological significance. These initial publications and later writings are typical of his pioneering investigations, which creatively appropriate diverse theological and philosophical sources (e.g., Ignatian spirituality, Thomas Aquinas, Catholic neoscholasticism, Kant, Hegel, and Heidegger). Notwithstanding their uncompromising rigor, most of his articles had a broadly pastoral concern to explore ways of recovering the meaning of Catholic doctrine in an intellectually plausible and contemporary idiom.

The density of Rahner's work is rooted in the subject matter itself. God, Rahner insisted, is not— and cannot—be an object for thought the way the things of our world are. But a person can know God by attending to the movement of knowing itself toward its objects, which reveals that human thinking always reaches beyond its immediate objects toward a further horizon. The movement of knowing, and the ultimate "goal" toward which it reaches, can be grasped only indirectly (or "transcendentally") as one's thinking turns back on itself reflexively. Rahner identified the elusive and final "term" of this dynamism of knowing with God, and argued that the same kind of movement toward God as "unobjectifiable" horizon is entailed in freedom and love.

By conceiving God, who always exceeds human reach, as the horizon of the movement of knowing, freedom, and love, Rahner emphasized that God is a mystery—a reality who is known and loved, but only reflexively and indirectly, as the ever-receding horizon of the human spirit. God remains a mystery in this sense even in self-communication to humanity through Jesus and the Holy Spirit. With this participation of God in an earthly history of human interconnectedness, something of God is anticipated—known reflexively and indirectly—at least implicitly whenever we know, choose, or love a specific being, particularly a neighbor in need. Conversely, God is implicitly rejected in every refusal of truth, freedom, and love.

Because it is often the good of a neighbor or the world, rather than God or Jesus which is directly affirmed or refused, it is quite possible that the one deciding will be unconscious or even deny that the act is a response to God. In either case, however, one turns toward or away from God and Jesus in turning one's mind and heart freely toward or away from the realities of the world.

Death is a universal and definitive manifestation of this free acceptance or rejection of God's self-communication ("grace"). In that sense, death is the culmination and fulfillment of a person's freedom, the final and definitive establishment of personal identity. It is not simply a transition to a new or continued temporal life. If there were no

Hence, death as a personal and spiritual phenomenon is not identical with the cessation of biological processes. For example, illness or medication can limit personal freedom well before the onset of clinically defined death. Moreover, insofar as all the engagements of one's life anticipate death, Rahner maintained that every moment of life participates in death. Hence he disputed the notion of death as a final decision if this is understood to be an occurrence only at the last moment.

The Christian tradition has emphasized the definitive and perduring character of personal existence by affirming the soul's survival after death. Rahner warned that this way of conceiving of death can be misleading if one imagines that the separation of soul and body, entails a denial of their intrinsic unity. The contemporary appreciation of the bodily constitution of human reality was anticipated by the scholastic doctrine of the soul as the "form" of the body and thus intrinsically, not merely accidentally, related to it. Personal identity is shaped by one's embodied and historical engagement with the material world. So the culmination of freedom in death must entail some sort of connection with that embodiment. Rahner's notion of God as mystery, beyond objectification in space and time, provides a framework for affirming a definitive unity with God that does not imagine the unity as a place or as a continuation of temporal existence. In the early essays, Rahner addressed the problem of conceiving the connection to embodiment, particularly in the "intermediate state" before the resurrection of the dead on judgment day, with the hypothesis that death initiates a deeper and more comprehensive "pancosmic" relationship to the material universe. In later essays, he recognized that it was not necessary to postulate an intermediate state with notions such as purgatory if one adopts Gisbert Greshake's conception of "resurrection in death," through which bodily reality is interiorized and transformed into an abiding perfection of the person's unity with God and with a transformed creation.

The Christian doctrine of death as the consequence and punishment of sin underscores its ambiguous duality and obscurity. If the integrity of human life were not wounded by sinfulness, perhaps death would be experienced as a peaceful culmination of each person's acceptance of God's self-communication in historical existence. But death can be a manifestation of a definitive "no" to truth and love, and so to God, the fullness of truth and love. Ironically, this results in a loss of self as well because it is unity with God's self-communication that makes definitive human fulfillment possible. In the "no," death becomes a manifestation of futile self-absorption and emptiness, and as such punishment of sin. Moreover, everyone experiences death as the manifestation of that possibility. As a consequence of sin, people experience death as a threat, loss, and limit, which impacts every moment of life. Because of this duality and ambiguity, even a "yes" to God involves surrender. Just as God's self-communication to humanity entailed fleshing out the divine in the humanity of Jesus, including surrender in death on the cross, so death-to-self is paradoxically intrinsic to each person's confrontation with biological death.

See also: Heidegger, Martin ; Kierkegaard, SØren ; Philosophy, Western

Bibliography

Phan, Peter C. Eternity in Time: A Study of Karl Rahner's Eschatology. Selinsgrove, PA: Susquehanna University Press, 1988.

Rahner, Karl. "The 'Intermediate State.'" Theological Investigations, translated by Margaret Kohl, Vol. 17. New York: Crossroad, 1981.

Rahner, Karl. "Ideas for a Theology of Death." Theological Investigations, translated by David Bourke, Vol. 13. New York: Crossroad, 1975.

Rahner, Karl, ed. "Death." Encyclopedia of Theology: The Concise Sacramentum Mundi. London: Burns and Cates, 1975 .

Rahner, Karl. On the Theology of Death, translated by Charles H. Henkey. New York: Herder and Herder, 1961.

ROBERT MASSON

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: