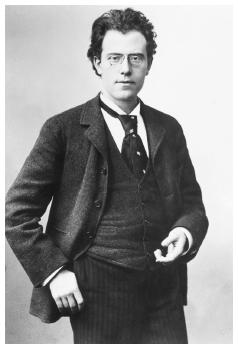

Mahler, Gustav

Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) was a Bohemian-born Austrian symphonic composer whose sprawling sonic canvases were often concerned with death, either as a spur to life or as a tragic and inconsolable end. Mahler grappled with mortality in his personal life as well as in his art.

The desperately comic and the searingly tragic coexist in the composer's ten numbered symphonies and many song cycles. His childhood shows the genesis of this strange pairing. In the building where Gustav lived as a child, the tavern owned by his father was adjacent to a funeral parlor put to frequent use by the Mahler family—eight of his fourteen siblings died before reaching adulthood. Mahler's father was a self-educated, somewhat brutal man, and fights between him and his cultured, delicate wife were common. Piano lessons were a way out of the daily misery for little Gustav, and before long, he was making up distinctive pieces of his own. Mahler's mature output seems an elaboration of that early conflation.

At age fifteen Gustav entered the Vienna Conservatory, where he received a diploma three years later. The early failure of his own music to win recognition sparked a remarkable conducting career that took Mahler to all the great opera houses and concert halls of Europe. Conducting earned him a fortune, but it also meant that composing, his first love, was relegated to the off-season. Throughout much of his life, Mahler composed in isolation in summer cottages.

From the beginning, Mahler declared that his music was not for his own time but for the future. An agnostic, he apparently saw long-term success as a real-world equivalent of immortality. "Mahler was a thoroughgoing child of the nineteenth century, an adherent of Nietzsche, and typically irreligious," the conductor Otto Klemperer recalled in his memoirs, adding that, in his music, Mahler evinced a "piety . . . not to be found in any church prayer-book." This appraisal is confirmed by the story of Mahler's conversion to Catholicism in 1897. Although his family was Jewish, Mahler was not observant, and when conversion was required in order to qualify as music director of the Vienna Court Opera—the most prestigious post in Europe—he swiftly acquiesced to baptism and confirmation, though he never again attended mass. Once on the podium, however, Mahler brought a renewed spirituality to many works, including Beethoven's Fidelio, which he almost single-handedly rescued from a reputation for tawdriness.

In 1902 Mahler married Alma Schindler, a woman nearly twenty years his junior. They had two daughters, and when Mahler set to work on his Kindertotenlieder —a song cycle on the death of children—Alma was outraged. As in a self-fulfilling prophecy, their oldest daughter died in 1907, capping a series of unrelenting tragedies for the composer. In that same year, Mahler was diagnosed with heart disease and dismissed from the Vienna Court Opera following a series of verbal attacks, some of them anti-Semitic. Mahler left for America, where he led the Metropolitan Opera from 1907 to 1910 and directed the New York Philharmonic from 1909 to 1911.

While in Vienna during the summer of 1910, Mahler discovered that Alma was having an affair with the architect Walter Gropius. He sought out Sigmund Freud, who met the composer at a train station in Holland and provided instant analysis, labeling him mother-fixated. Freud later declared his analysis successful, and indeed Mahler claimed in correspondence to have enjoyed an improved relationship with his wife. But it did nothing to stop the deterioration of Mahler's health.

The Mahler biographer Henry-Louis de La Grange has effectively contradicted the popular image of Mahler as congenitally ill. A small man, Mahler was nonetheless physically active, an avid hiker and swimmer throughout most of his life. Nonetheless, he was a man drunk on work, and he grew more inebriated with age. His response to the fatigue and illness was often simply to work more. In 1901, for example, he collapsed after conducting, in the same day, a full-length opera and a symphony concert. He immediately set to work on his Symphony no. 5, which begins with a funeral march.

Mahler's symphonies divide into early, middle, and late periods, respectively comprising the first four symphonies; the fifth, sixth, and seventh symphonies; and the eighth and ninth, plus "Das Lied von der Erde" and the unfinished Tenth Symphony.

Symphony no. 1 in D is subtitled the "Titan," not after the Greek demigods but after a novel of the same name by Jean Paul Richter. The third movement turns "Frère Jacques" into a minor-mode funeral march. Symphony no. 2 moved the symphonic form into entirely new territory. It was longer and required more forces, including a chorus and vocal soloist, and its emotional range was vast. Though subtitled "Resurrection," its texts make no religious claims. Mahler's Symphony no. 3 remains the longest piece in the mainstream symphonic repertory. Its ninety-five minutes open with a massive movement that swiftly swings from moody loneliness to martial pomp, from brawling play to near-mute meditation. An ethereal final adagio is followed by four inner movements of contrasting content, including a quiet, nine-minute solo for mezzo-soprano to a text by Nietzsche extolling the depth of human tragedy. Symphony no. 4, slender by Mahler's standards, concluded Mahler's first period, in which song played an important role.

Mahler's next three symphonies were wholly instrumental. Symphony no. 5 is easily read as a backward glance at a man's life. It begins with the most magnificent of orchestral funeral marches, announced by a brilliant trumpet solo, and then slowly moves through movements of anguish and struggle toward the penultimate "Adagietto" (Mahler's most famous excerpt), a wordless love song, and finally to the last movement, filled with the promise of youth. Symphony no. 6, subtitled "Tragic," was formally the composer's most tightly structured, and no. 7, subtitled "Nightsong," is, in its odd last movement, the composer at his most parodistic. In no. 8, "Symphony of a Thousand," Mahler returned to the human voice as symphonic instrument, setting texts from the Catholic liturgy and Goethe.

For symphonists, nine is the number to fear. It took on special status for composers when Beethoven died after composing only nine symphonies. From Beethoven on, nine had mystical significance. Schubert died after writing nine symphonies, so did Dvorak and Bruckner. Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Brahms did not get near that number before they shuffled off the mortal coil.

Mahler completed his Symphony no. 8 in 1906. In 1907 came his triple calamities: the death of his daughter, his unamicable separation from Vienna Opera, and the diagnosis of heart disease. It was not a good time to compose a symphony whose number cried death. Mahler thought he could skirt the issue by writing an unnumbered symphony that would function as his ninth without carrying the dreaded digit. Thus, Mahler composed "Das Lied von der Erde" ("Song of the Earth"), a massive song cycle for voices and orchestra, that was in every way—except the number—his Ninth Symphony.

Fate read his Symphony no. 9 as the last and would not allow him to finish a tenth. (The one movement he completed is generally performed as a fragment.) In February 1911 Mahler led the New York Philharmonic one last time at Carnegie Hall and then returned to Vienna, where he died three months later of bacterial endocarditis. The twenty-three minutes of the Ninth's last movement, which have been described as "ephemeral" and "diaphanous," weep without apology. Somewhere near the middle of this very slow (Molto adagio) movement comes a jittery harp figure that mimics the composer's coronary arrhythmia.

In length, the size of the forces required, and emotional scope, Mahler's symphonies have rarely been equaled and never surpassed. It is difficult not to see this inflation as the composer's struggle against mortality. If the world was temporary and afterlife improbable, why not postulate immortality through art? "A symphony should be like the world," Mahler said to fellow composer Jan Sibelius, "It should embrace everything!"

See also: Folk Music ; Music, Classical ; Operatic Death

Bibliography

Cook, Deryck. Gustav Mahler: An Introduction to His Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Floros, Constantin. Gustav Mahler: The Symphonies, edited by Reinhold G. Pauly and translated by Vernon Wicker. Portland, OR: Timber Press, 1997.

La Grange, Henry-Louis de. Mahler. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1973.

Lebrecht, Norman. Mahler Remembered. New York: W.W. Norton, 1987.

Mahler-Werfel, Alma. The Diaries, translated by Antony Beaumont. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000.

Mitchell, Donald, and Andrew Nicholson, eds. The Mahler Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

KENNETH LAFAVE