Burial Grounds

Three kinds of gravescapes—that is, memorials and the landscapes containing them—have dominated the funerary scene in North America from colonial times to the present. The first, the graveyard, almost invariably is located in towns and cities, typically adjoined to a church and operated gratis or for a nominal fee by members of the congregation. The second, the rural cemetery, is usually situated at the outskirts of towns and cities and is generally owned and managed by its patrons. The third, the lawn cemetery, is typically located away from towns and cities and ordinarily is managed by professional superintendents and owned by private corporations. These locations are generalities; in the nineteenth century both the rural cemetery and the lawn cemetery began to be integrated into the towns and cities that grew up around them.

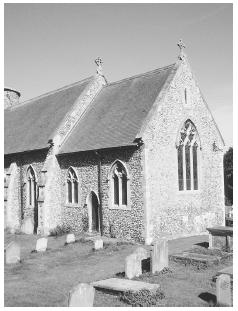

The Graveyard

From the beginning of colonization and for many years thereafter, Euroamerican gravescapes in North America uniformly presented visitors with a powerful imperative: Remember death, for the time of judgment is at hand. The graveyard serves as a convenient place to dispose of the dead; however, its more significant purpose derives from its formal capacity to evoke or establish memory of death, which serves to remind the living of their own fragility and urgent need to prepare for death. Locating the dead among the living thus helps to ensure that the living will witness the gravescape's message regularly as a reminder "to manifest that this world is not their home" and "that heaven is a reality" (Morris 1997, p. 65). Devaluation of all things accentuating the temporal life is the starting point for a cultural logic that embraces the view that "the life of the body is no longer the real life, and the negation of this life is the beginning rather than the end" (Marcuse 1959, p. 68).

Inscriptions and iconography continually reinforce these imperatives by deemphasizing temporal life and emphasizing the necessity of attending to the demands of eternal judgment. Only rarely, for example, do the memorials indicative of this perspective provide viewers with information beyond the deceased's name, date of death, and date of birth. Icons reminiscent of death (for example, skulls, crossed bones, and the remarkably popular winged death's head) almost invariably appear at or near the center of the viewer's focus, while icons associated with life appear on the periphery. Popular mottos like memento mori ("remember death") and fugit hora ("time flies," or more literally "hours flee") provide viewers with explicit instruction.

Certain actions run contrary to the values that give this gravescape its meaning. For example, locating the dead away from the living, enclosing burial grounds with fences as if to separate the living from the dead, decorating and adorning the gravescape, or ordering the graveyard according to dictates of efficiency and structural linearity. The constant struggles to embrace and encourage others to embrace the view that life is nothing more than preparation for death demands constant attention if one seeks to merit eternal bliss and avoid eternal damnation. This view thus unceasingly insists upon a clear and distinct separation of "real life" (spiritual life, eternal life) from "illusory life" (physical life; the liminal, transitory existence one leads in the here and now). The formal unity of memorials in this gravescape both ensures its identity and energizes and sustains its rhetorical and cultural purpose.

Even from a distance the common size and shape of such memorials speak to visitors of their purpose. Although the graveyard provides ample space for variation, an overwhelming majority of the memorials belonging to this tradition are relatively modest structures (between one and five feet in height and width and between two and five inches thick), and most are variations of two shapes: single and triple arches. Single arch memorials are small, smoothed slabs with three squared sides and a convex or squared crown. Triple arch memorials are also small, smoothed slabs with three squared sides but feature smaller arches on either side of a single large arch, which gives the impression of a single panel with a convex crown

The Rural Cemetery

For citizens possessed of quite different sensibilities, the graveyard was a continual source of discontentment until the introduction of a cemeterial form more suited to their values. That form, which emerged on September 24, 1830, with the consecration of Boston's Mount Auburn Cemetery, signaled the emanation of a radically different kind of cemetery. Rather than a churchyard filled with graves, this new gravescape would be a place from which the living would be able to derive pleasure, emotional satisfaction, and instruction on how best to live life in harmony with art and nature.

Judging from the rapid emergence of rural cemeteries subsequent to the establishment of Mount Auburn, as well as Mount Auburn's immediate popularity, this new cemeterial form quickly lived up to its advocates' expectations. Within a matter of months travelers from near and far began to make "pilgrimages to the Athens of New England, solely to see the realization of their long cherished dream of a resting place for the dead, at once sacred from profanation, dear to the memory, and captivating to the imagination" (Downing 1974, p. 154). Part of the reason for Mount Auburn's immediate popularity was its novelty. Yet Mount Auburn remained remarkably popular throughout the nineteenth century and continues to attract a large number of visitors into the twenty-first century.

Moreover, within a few short years rural cemeteries had become the dominant gravescape, and seemingly every rural cemetery fostered one or more guidebooks, each of which provided prospective visitors with a detailed description of the cemetery and a walking tour designed to conduct visitors along the most informative and beautiful areas. "In their mid-century heyday, before the creation of public parks," as the scholar Blanche Linden-Ward has observed, "these green pastoral places also functioned as 'pleasure grounds' for the general public" (Linden-Ward 1989, p. 293). Mount Auburn "presented [and still presents] visitors with a programmed sequence of sensory experiences, primarily visual, intended to elicit specific emotions, especially the so-called pleasures of melancholy that particularly appealed to contemporary romantic sensibilities" (p. 295).

The owners of rural cemeteries played a significant role in the effort to capture the hearts and imaginations of visitors insofar as they sought to ensure that visitors would encounter nature's many splendors. They accomplished this not only by taking great care to select sites that would engender just such sentiments but also by purchasing and importing wide varieties of exotic shrubs, bushes, flowers, and trees. Both from within the grave-scape and from a distance, rural cemeteries thus frequently appear to be lush, albeit carefully constructed, nature preserves.

Promoting a love of nature, however, was only a portion of what patrons sought to accomplish in their new gravescape. "The true secret of the attraction," America's preeminent nineteenth-century landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing insisted, lies not only "in the natural beauty of the sites," but also "in the tasteful and harmonious embellishment of these sites by art." Thus, "a visit to one of these spots has the united charm of nature and art, the double wealth of rural and moral association. It awakens at the same moment, the feeling of human sympathy and the love of natural beauty, implanted in every heart" (Downing 1974, p. 155). To effect this union of nature and art, cemetery owners went to great lengths—and often enormous costs—to commission and obtain aesthetically appealing objects to adorn the cemetery and to set a standard for those wishing to erect memorials to their deceased friends and relatives.

In this way cemetery owners recommended by example that memorials were to be works of art. Even the smallest rural cemeteries suggested this much by creating, at the very least, elaborate entrance gates to greet visitors so that their cemeteries would help to create "a distinct resonance between the landscape design of the 'rural' cemetery and recurring themes in much of the literary and material culture of that era" (Linden-Ward 1989, p. 295).

The Lawn Cemetery

The rural cemetery clearly satisfied the values and needs of many people; yet a significant segment of the population found this gravescape too ornate, too sentimental, too individualized, and too expensive. Even Andrew Jackson Downing, who had long been a proponent of the rural cemetery, publicly lamented that the natural beauty of the rural cemetery was severely diminished "by the most violent bad taste; we mean the hideous ironmongery, which [rural cemeteries] all more or less display. . . . Fantastic conceits and gimeracks in iron might be pardonable as adornments of the balustrade of a circus or a temple of Comus," he continued, "but how reasonable beings can tolerate them as inclosures to the quiet grave of a family, and in such scenes of sylvan beauty, is mountain high above our comprehension" (Downing 1974, p. 156).

Largely in response to these criticisms, in 1855 the owners of Cincinnati's Spring Grove Cemetery instructed their superintendent, Adolph Strauch, to remove many of the features included when John Notman initially designed Spring Grove as a rural cemetery. In redesigning the cemetery, however, Strauch not only eliminated features typically associated with rural cemeteries, he also created a new cemeterial form that specifically reflected and articulated a very different set of needs and values.

In many ways what Strauch created and what lawn cemeteries have become is a matter of absence rather than of presence. The absence of raised mounds, ornate entrance gates, individualized gardens, iron fencing, vertical markers, works of art dedicated to specific patrons, freedom of expression in erecting and decorating individual or family plots, and cooperative ownership through patronage produces a space that disassociates itself not only from previous traditions but also from death itself. This is not to say that lawn cemeteries are devoid of ornamentation, as they often contain a variety of ornamental features. Nevertheless, as one early advocate remarked, lawn cemeteries seek to eliminate "all things that suggest death, sorrow, or pain" (Farrell 1980, p. 120).

Rather than a gravescape designed to remind the living of their need to prepare for death or a gravescape crafted into a sylvan scene calculated to allow mourners and others to deal with their loss homeopathically, the lawn cemetery provides visitors with an unimpeded view. Its primary characteristics include efficiency, centralized management, markers that are either flush with or depressed into the ground, and explicit rules and regulations.

Yet to patrons the lawn cemetery affords several distinct advantages. First, it provides visitors with an open vista, unobstructed by fences, memorials, and trees. Second, it allows cemetery superintendents to make the most efficient use of the land in the cemetery because available land is generally laid out in a grid so that no areas fail to come under a general plan. Third, by eliminating fences, hedges, trees, and other things associated with the rural cemetery and by requiring markers to be small enough to be level or nearly level with the ground, this gravescape does not appear to be a gravescape at all.

Although lawn cemeteries did not capture people's imaginations as the rural cemetery had in the mid–nineteenth century, they did rapidly increase in number. As of the twenty-first century they are considered among the most common kind of gravescape in the United States.

See also: Cemeteries and Cemetery Reform ; Cemeteries, War ; Funeral Industry ; Lawn Garden Cemeteries

Bibliography

Downing, Andrew Jackson. "Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens." In George W. Curtis ed., Rural Essays by Andrew Jackson Downing. New York: Da Capo, 1974.

French, Stanley. "The Cemetery As Cultural Institution: The Establishment of Mount Auburn and the 'Rural Cemetery' Movement." In David E. Stannard ed., Death in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1974.

Linden, Blanche M. G. "The Willow Tree and Urn Motif: Changing Ideas about Death and Nature." Markers 1 (1979–1980):149–155.

Linden-Ward, Blanche. "Strange but Genteel Pleasure Grounds: Tourist and Leisure Uses of Nineteenth Century Cemeteries." In Richard E. Meyer ed., Cemeteries and Gravemarkers: Voices of American Culture. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Research Press, 1989.

Ludwig, Allan I. Graven Images: New England Stonecarving and Its Images, 1650–1815. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1966.

Marcuse, Herbert. "The Ideology of Death." In Herman Feifel ed., The Meaning of Death. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1959.

Morris, Richard. Sinners, Lovers, and Heroes: An Essay on Memorializing in Three American Cultures. Albany: SUNY Press, 1997.

Tashjian, Dickran, and Ann Tashjian. Memorials for Children of Change: The Art of Early New England Stone Carving. Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1974.

RICHARD MORRIS

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: