Ars Moriendi

The Ars Moriendi, or "art of dying," is a body of Christian literature that provided practical guidance for the dying and those attending them. These manuals informed the dying about what to expect, and prescribed prayers, actions, and attitudes that would lead to a "good death" and salvation. The first such works appeared in Europe during the early fifteenth century, and they initiated a remarkably flexible genre of Christian writing that lasted well into the eighteenth century.

Fifteenth-Century Beginnings

By 1400 the Christian tradition had well-established beliefs and practices concerning death, dying, and the afterlife. The Ars Moriendi packaged many of these into a new, concise format. In particular, it expanded the rite for priests visiting the sick into a manual for both clergy and laypeople. Disease, war, and changes in theology and Church policies formed the background for this new work. The Black Death had devastated Europe in the previous century, and its recurrences along with other diseases continued to cut life short. Wars and violence added to the death toll. The Hundred Years' War (1337–1453) between France and England was the era's largest conflict, but its violence and political instability mirrored many local conflicts. The fragility of life under these conditions coincided with a theological shift noted by the historian Philippe Ariès whereas the early Middle Ages emphasized humanity's collective judgment at the end of time, by the fifteenth century attention focused on individual judgment immediately after death. One's own death and judgment thus became urgent issues that required preparation.

To meet this need, the Ars Moriendi emerged as part of the Church authorities' program for educating priests and laypeople. In the fourteenth century catechisms began to appear, and handbooks were drafted to prepare priests for parish work, including ministry to the dying. The Council of Constance (1414–1418) provided the occasion for the Ars Moriendi's composition. Jean Gerson, chancellor of the University of Paris, brought to the council his brief essay, De arte moriendi. This work became the basis for the anonymous Ars Moriendi treatise that soon appeared, perhaps at the council itself. From Constance, the established networks of the Dominicans and Franciscans assured that the new work spread quickly throughout Europe.

The Ars Moriendi survives in two different versions. The first is a longer treatise of six chapters that prescribes rites and prayers to be used at the time of death. The second is a brief, illustrated book that shows the dying person's struggle with temptations before attaining a good death. As Mary Catharine O'Connor argued in her book The Arts of Dying Well, the longer treatise was composed earlier and the shorter version is an abridgment that adapts and illustrates the treatise's second chapter. Yet O'Connor also noted the brief version's artistic originality. For while many deathbed images pre-date the Ars Moriendi, never before had deathbed scenes been linked into a series "with a sort of story, or at least connected action, running through them" (O'Connor 1966, p. 116). The longer Latin treatise and its many translations survive in manuscripts and printed editions throughout Europe. The illustrated version circulated mainly as "block books," where pictures and text were printed from carved blocks of wood; Harry W. Rylands (1881) and Florence Bayard reproduced two of these editions.

An English translation of the longer treatise appeared around 1450 under the title The Book of the Craft of Dying. The first chapter praises the deaths of good Christians and repentant sinners who die "gladly and wilfully" in God (Comper 1977, p. 7). Because the best preparation for a good death is a good life, Christians should "live in such wise . . . that they may die safely, every hour, when God will" (Comper 1977, p. 9). Yet the treatise focuses on dying and assumes that deathbed repentance can yield salvation.

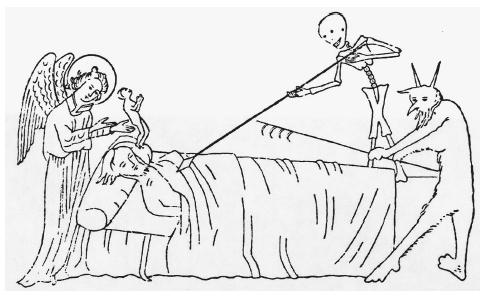

The second chapter is the treatise's longest and most original section. It confronts the dying with five temptations and their corresponding "inspirations" or remedies: (1) temptation against faith versus reaffirmation of faith; (2) temptation to despair versus hope for forgiveness; (3) temptation to impatience versus charity and patience; (4) temptation to vainglory or complacency versus humility and recollection of sins; and (5) temptation to avarice or attachment to family and property versus detachment. This scheme accounts for ten of the eleven illustrations in the block book Ars Moriendi , where five scenes depict demons tempting the dying man and five others portray angels offering their inspirations.

Of special importance are the second and fourth temptations, which test the dying person's sense of guilt and self-worth with two sharply contrasting states: an awareness of one's sins that places one beyond redemption and a confidence in one's merits that sees no need for forgiveness. Both despair and complacent self-confidence can be damning because they rule out repentance. For this reason the corresponding remedies encourage the dying to acknowledge their sins in hope because all sins can be forgiven through contrition and Christ's saving death.

As Ariès notes, throughout all five temptations, the Ars Moriendi emphasizes the active role of the dying in freely deciding their destinies. For only their free consent to the demonic temptations or angelic inspirations determines whether they are saved or damned.

The third chapter of the longer treatise prescribes "interrogations" or questions that lead the dying to reaffirm their faith, to repent their sins, and to commit themselves fully to Christ's passion and death. The fourth chapter asks the dying to imitate Christ's actions on the cross and provides prayers for "a clear end" and the "everlasting bliss that is the reward of holy dying" (Comper 1977, p. 31). In the fifth chapter the emphasis shifts to those who assist the dying, including family and friends. They are to follow the earlier prescriptions, present the dying with images of the crucifix and saints, and encourage them to repent, receive the sacraments, and draw up a testament disposing of their possessions. In the process, the attendants are

The illustrated Ars Moriendi concludes with a triumphant image of the good death. The dying man is at the center of a crowded scene. A priest helps him hold a candle in his right hand as he breathes his last. An angel receives his soul in the form of a naked child, while the demons below vent their frustration at losing this battle. A crucifixion scene appears to the side, with Mary, John, and other saints. This idealized portrait thus completes the "art of dying well."

The Later Tradition

The two original versions of the Ars Moriendi initiated a long tradition of Christian works on preparation for death. This tradition was wide enough to accommodate not only Roman Catholic writers but also Renaissance humanists and Protestant reformers—all of whom adapted the Ars Moriendi to their specific historical circumstances. Yet nearly all of these authors agreed on one basic change: They placed the "art of dying" within a broader "art of living," which itself required a consistent memento mori, or awareness of and preparation for one's own death.

The Ars Moriendi tradition remained strong within the Roman Catholic communities. In his 1995 book From Madrid to Purgatory, Carlos M. N. Eire documented the tradition's influence in Spain where the Ars Moriendi shaped published accounts of the deaths of St. Teresa of Avila (1582) and King Philip II (1598). In his 1976 study of 236 Ars Moriendi publications in France, Daniel Roche found that their production peaked in the 1670s and declined during the period from 1750 to 1799. He also noted the Jesuits' leading role in writing Catholic Ars Moriendi texts, with sixty authors in France alone.

Perhaps the era's most enduring Catholic text was composed in Italy by Robert Bellarmine, the prolific Jesuit author and cardinal of the church. In 1619 Bellarmine wrote his last work, The Art of Dying Well . The first of its two books describes how to live well as the essential preparation for a good death. It discusses Christian virtues, Gospel texts, and prayers, and comments at length on the seven sacraments as integral to Christian living and dying. The second book, The Art of Dying Well As Death Draws Near, recommends meditating on death, judgment, hell, and heaven, and discusses the sacraments of penance, Eucharist, and extreme unction or the anointing of the sick with oil. Bellarmine then presents the familiar deathbed temptations and ways to counter them and console the dying, and gives examples of those who die well and those who do not. Throughout, Bellarmine reflects a continuing fear of dying suddenly and unprepared. Hence he focuses on living well and meditating on death as leading to salvation even if one dies unexpectedly. To highlight the benefits of dying consciously and well prepared, he claims that prisoners facing execution are "fortunate"; knowing they will die, they can confess their sins, receive the Eucharist, and pray with their minds more alert and unclouded by illness. These prisoners thus enjoy a privileged opportunity to die well.

In 1534 the Christian humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam wrote a treatise that appeared in English in 1538 as Preparation to Death. He urges his readers to live rightly as the best preparation for death. He also seeks a balance between warning and comforting the dying so that they will be neither flattered into arrogant self-confidence nor driven to despair; repentance is necessary, and forgiveness is always available through Christ. Erasmus dramatizes the deathbed scene in a dialogue between the Devil and the dying Man. The Devil offers temptations to which the Man replies clearly and confidently; having mastered the arts of living and dying, the Man is well prepared for this confrontation. While recognizing the importance of sacramental confession and communion, Erasmus says not to worry if a priest cannot be present; the dying may confess directly to God who gives salvation without the sacraments if "faith and a glad will be present" (Atkinson 1992, p. 56).

The Ars Moriendi tradition in England has been especially well documented. It includes translations of Roman Catholic works by Petrus Luccensis and the Jesuit Gaspar Loarte; Thomas Lupset's humanistic Way of Dying Well; and Thomas Becon's Calvinist The Sick Man's Salve . But one literary masterpiece stands out, which is Jeremy Taylor's The Rule and Exercises of Holy Dying.

When Taylor published Holy Dying in 1651, he described it as "the first entire body of directions for sick and dying people" (Taylor 1977, p. xiii) to be published in the Church of England. This Anglican focus allowed Taylor to reject some elements of the Roman Catholic Ars Moriendi and to retain others. For example, he ridicules deathbed repentance but affirms traditional practices for dying well; by themselves the protocols of dying are "not enough to pass us into paradise," but if "done foolishly, [they are] enough to send us to hell" (Taylor 1977, p. 43). For Taylor the good death completes a good life, but even the best Christian requires the prescribed prayers, penance, and Eucharist at the hour of death. And Holy Dying elegantly lays out a program for living and dying well. Its first two chapters remind readers of their mortality and urge them to live in light of this awareness. In the third chapter, Taylor describes two temptations of the sick and dying: impatience and the fear of death itself. Chapter four leads the dying through exercises of patience and repentance as they await their "clergy-guides," whose ministry is described in chapter five. This bare summary misses both the richness of Taylor's prose and the caring, pastoral tone that led Nancy Lee Beaty, author of The Craft of Dying, to consider Holy Dying, the "artistic climax" of the English Ars Moriendi tradition (Beaty 1970, p. 197).

Susan Karant-Nunn, in her 1997 book The Reformation of Ritual, documented the persistence of the Ars Moriendi tradition in the "Lutheran Art of Dying" in Germany during the late sixteenth century. Although the Reformers eliminated devotion to the saints and the sacraments of penance and anointing with oil, Lutheran pastors continued to instruct the dying and to urge them to repent, confess, and receive the Eucharist. Martin Moller's Manual on Preparing for Death (1593) gives detailed directions for this revised art of dying.

Karant-Nunn's analysis can be extended into the eighteenth century. In 1728 Johann Friedrich Starck [or Stark], a Pietist clergyman in the German Lutheran church, treated dying at length in his Tägliches Hand-Buch in guten und bösen Tagen. Frequently reprinted into the twentieth century, the Hand-Book became one of the most widely circulated prayer books in Germany. It also thrived among German-speaking Americans, with ten editions in Pennsylvania between 1812 and 1829, and an 1855 English translation, Daily Hand-Book for Days of Rejoicing and of Sorrow.

The book contains four major sections: prayers and hymns for the healthy, the afflicted, the sick, and the dying. As the fourth section seeks "a calm, gentle, rational and blissful end," it adapts core themes from the Ars Moriendi tradition: the dying must consider God's judgment, forgive others and seek forgiveness, take leave of family and friends, commend themselves to God, and "resolve to die in Jesus Christ." While demons no longer appear at the deathbed, the temptation to despair remains as the dying person's sins present themselves to "frighten, condemn, and accuse." The familiar remedy of contrition and forgiveness through Christ's passion comforts the dying. Starck offers a rich compendium of "verses, texts and prayers" for bystanders to use in comforting the dying, and for the dying themselves. A confident, even joyful, approach to death dominates these prayers, as the dying person prays, "Lord Jesus, I die for thee, I live for thee, dead and living I am thine. Who dies thus, dies well."

Ars Moriendi in the Twenty-First Century

Starck's Hand-Book suggests what became of the Ars Moriendi tradition. It did not simply disappear. Rather, its assimilation to Christian "arts of living" eventually led to decreasing emphasis on the deathbed, and with it the decline of a distinct genre devoted to the hour of death. The art of dying then found a place within more broadly conceived prayer books and ritual manuals, where it remains today (e.g., the "Ministration in Time of Death" in the Episcopal Church's Book of Common Prayer). The Ars Moriendi has thus returned to its origins. Having emerged from late medieval prayer and liturgy, it faded back into the matrix of Christian prayer and practice in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The Ars Moriendi suggests useful questions for twenty-first century approaches to dying. During its long run, the Ars Moriendi ritualized the pain and grief of dying into the conventional and manageable forms of Christian belief, prayer, and practice. In what ways do current clinical and religious practices ritualize dying? Do these practices place dying persons at the center of attention, or do they marginalize and isolate them? What beliefs and commitments guide current approaches to dying? Although the Ars Moriendi's convictions about death and afterlife are no longer universally shared, might they still speak to believers within Christian churches and their pastoral care programs? What about the views and expectations of those who are committed to other religious traditions or are wholly secular? In light of America's diversity, is it possible—or desirable—to construct one image of the good death and what it might mean to die well? Or might it be preferable to mark out images of several good deaths and to develop new "arts of dying" informed by these? Hospice and palliative care may provide the most appropriate context for engaging these questions. And the Ars Moriendi tradition offers a valuable historical analogue and framework for posing them.

See also: AriÈs, Philippe ; Black Death ; Christian Death Rites, History OF ; Good Death, The ; Memento Mori ; Taylor, Jeremy ; Visual Arts

Bibliography

Ariès, Philippe. The Hour of Our Death , translated by Helen Weaver. New York: Knopf, 1981.

Atkinson, David William. The English Ars Moriendi . New York: Peter Lang, 1992.

Beaty, Nancy Lee. The Craft of Dying: A Study in the Literary Tradition of the Ars Moriendi in England. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1970.

Bellarmine, Robert. "The Art of Dying Well." In Spiritual Writings, translated and edited by John Patrick Donnelly and Roland J. Teske. New York: Paulist Press, 1989.

Comper, Frances M. M. The Book of the Craft of Dying and Other Early English Tracts concerning Death . New York: Arno Press, 1977.

Duclow, Donald F. "Dying Well: The Ars Moriendi and the Dormition of the Virgin." In Edelgard E. DuBruck and Barbara Gusick eds., Death and Dying in the Middle Ages. New York: Peter Lang, 1999.

Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, c. 1400–c. 1580. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992.

Eire, Carlos M. N. From Madrid to Purgatory: The Art and Craft of Dying in Sixteenth-Century Spain . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Karant-Nunn, Susan C. The Reformation of Ritual: An Interpretation of Early Modern Germany . London: Routledge, 1997.

O'Connor, Mary Catharine. The Arts of Dying Well: The Development of the Ars Moriendi . New York: AMS Press, 1966.

Rylands, Harry W. The Ars Moriendi (Editio Princeps, circa 1450): A Reproduction of the Copy in the British Museum . London: Holbein Society, 1881.

Starck [Stark], Johann Friedrich. Daily Hand-Book for Days of Rejoicing and of Sorrow . Philadelphia: I. Kohler, 1855.

Taylor, Jeremy. The Rule and Exercises of Holy Dying . New York: Arno Press, 1977.

DONALD F. DUCLOW

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: